How-to Guide

Part 2: Tensor Operations, Building an LLM from Scratch in Rust

December 22, 2025

In Part 2 of this series, we move beyond tokenization to explore the mathematical heart of the model: tensors. Here, we show how every operation inside a transformer, from attention to layer normalization, boils down to simple computations on multidimensional arrays of numbers.

By building a basic tensor library from scratch in Rust, readers see how transformers aren’t magic but rather elegantly constructed systems shaped by how math works on real computers. This foundation powers the rest of Feste, our GPT-2 style language model trained on Shakespeare’s works.

In Part 1, we converted text into numbers. Now we need to do something with those numbers.

You've probably heard that transformers work through matrix multiplication and attention. Those words are real, but they're abstractions. Underneath everything is tensor math: operations on multidimensional arrays of numbers. Every operation in a language model comes down to tensors. Attention is matrix multiplication on tensors. Layer normalization is statistics on tensor dimensions. Embeddings are lookups that produce tensors.

Most frameworks abstract tensors away so completely that you never think about the actual data. You call a function and trust it works. But understanding how tensors are organized in memory matters for understanding how transformers work. The shape of your data, how values are laid out, whether they sit next to each other or are scattered around—these aren't just implementation details. They shape what operations are possible and how the architecture comes together.

There's something genuinely fun about digging this deep. When you build a tensor library from scratch instead of importing one, you see why transformers look the way they do. It's not magic or arbitrary design choices. It's shaped by the actual constraints of how math works on computers.

This chapter implements the tensor library that powers everything else in Feste, our GPT-2 style transformer built in Rust and trained on Shakespeare's complete works. It's not optimized for speed. It's built to be clear about what's happening underneath.

What is a Tensor?

A tensor is a multidimensional array of numbers. The term comes from physics, where it described stress and strain on materials. Machine learning borrowed the word but uses it more loosely. It just means an array of any dimensionality: scalars (single numbers, zero dimensions), vectors (lists, one dimension), matrices (grids, two dimensions with rows and columns), or anything with more dimensions.

A 3D tensor adds depth like a cube. A 4D tensor is like multiple cubes stacked together. Each dimension is an axis you can move along in the data.

Transformer models typically work with 3D and 4D tensors. When the model processes "To be or not to be", it converts those tokens into a 3D block of numbers with one dimension for position in the sequence, another for position in each token's representation, and a third if we're processing multiple sentences at once. When computing attention (deciding which tokens should pay attention to which other tokens), the model needs another dimension to track multiple attention heads working in parallel, giving us 4D tensors.

Higher-dimensional tensors are mathematically possible, but transformers don't naturally need them. The architecture works with batches of 4D tensors. If you need to process more data, you just make the batch dimension bigger instead of adding new dimensions. This keeps everything simpler. Our implementation stores three pieces of information:

pub struct Tensor {

pub data: Vec<f32>, // Flat array of values

pub shape: Vec<usize>, // Dimensions like [2, 3, 4]

pub strides: Vec<usize>, // Step sizes for indexing

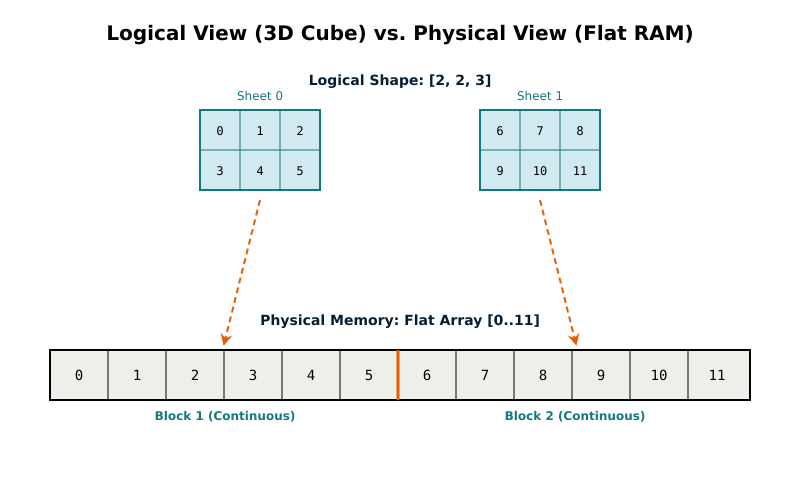

}All tensor data lives as a single flat list of numbers, no matter how many dimensions the tensor has. You think of a matrix as having rows and columns, but the computer stores it as one long sequence.

Take a 2×3 matrix (2 rows, 3 columns). You visualize it as:

[a b c]

[d e f]

In memory it lives as a flat list: [a, b, c, d, e, f]. Six numbers in a row. The computer doesn't store the grid structure, just a line of values.

The shape field tells you how to interpret those flat values. A shape of [2, 3] means two rows and three columns. When you see [a, b, c, d, e, f] with shape [2, 3], you read the first three values as row one and the next three as row two.

A 3D tensor with shape [2, 3, 4] still uses one flat list of 24 numbers (2 × 3 × 4 = 24). The shape tells you it's organized as 2 groups, each containing 3 rows of 4 values.

The strides field tells us how to navigate this flat array as if it were multidimensional. A stride tells you how many positions to jump in the flat array when you move one step along a dimension. For shape [2, 3], strides are [3, 1]: jump 3 positions to move down a row, jump 1 to move across a column. For shape [2, 3, 4], strides would be [12, 4, 1]: jump 12 to move between groups, jump 4 to move between rows, and jump 1 to move between columns.

This matters because modern CPUs process contiguous memory quickly. When values sit next to each other, the CPU loads them in chunks and processes them efficiently. Random memory access is much slower. Keeping everything in one flat array lets the CPU work fast.

Creating Tensors

We need ways to make tensors. The simplest approach passes data and a shape:

let tensor = Tensor::new(vec![1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0], vec![2, 2]);This creates a 2×2 matrix with four values arranged as two rows and two columns. The code checks that the data size matches the shape. Pass four values but claim shape [2, 3] and it panics. Better to fail immediately than silently corrupt data.

Sometimes you need tensors filled with specific patterns. Zeros are common:

let zeros = Tensor::zeros(vec![3, 4]);This makes a 3×4 matrix of zeros, twelve zeros total interpreted as three rows of four columns.

Sequential numbers are useful for testing:

let range = Tensor::arange(0, 10);This produces [0.0, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, 9.0], a vector of ten values counting from zero to nine.

Nothing complicated here. We allocate memory, fill it with values, and track the shape.

Core Operations

Feste implements the core tensor operations needed for a transformer: matrix multiplication, addition, reshaping, and reduction operations like sum and mean. It doesn't implement every possible tensor operation, and it's not optimized for speed at scale.

Matrix multiplication gets special attention because it dominates compute time. It uses cache blocking and parallel execution. Other expensive operations like softmax and normalization run in parallel too, but with simpler implementations. Memory operations like reshape and transpose just rearrange data without much optimization.

We'll cover the fundamental operations first, then the transformer-specific ones like softmax and normalization, then helpers like broadcasting and masking.

Matrix Multiplication: The Core Operation

Matrix multiplication is the single most important operation in neural networks.

A neural network takes input numbers and transforms them through layers to produce output numbers. Each layer applies learned patterns (the weights) to the input. That transformation happens through matrix multiplication. Every major operation in a transformer boils down to multiplying matrices.

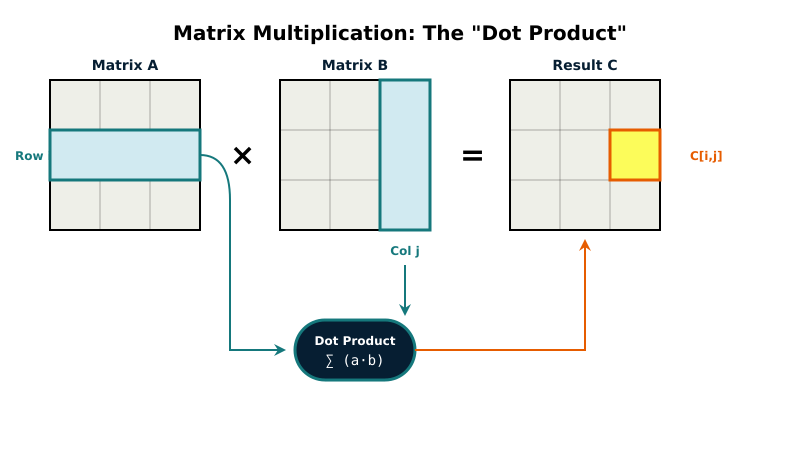

Say you want to multiply matrix A (m rows by k columns) by matrix B (k rows by n columns). The result C has m rows by n columns. To compute each element of C:

C[i,j] = A[i,0]*B[0,j] + A[i,1]*B[1,j] + ... + A[i,k-1]*B[k-1,j]

Take row i from A and column j from B. Multiply the first element from the row by the first element from the column, then the second by the second, and so on. Add all those products together. That sum is the value for position [i,j] in the result.

The straightforward implementation uses three nested loops:

for i in 0..m {

for j in 0..n {

let mut sum = 0.0;

for l in 0..k {

sum += a[i * k + l] * b[l * n + j];

}

result[i * n + j] = sum;

}

}This works for small matrices. The outer loop picks which row of A, the middle loop picks which column of B, the inner loop does the multiply-and-add. But large matrices expose two problems.

First, cache misses. As l changes, b[l * n + j] jumps around memory. The CPU loads a chunk of nearby values (a cache line), uses one, then loads a completely different chunk for the next value. Constantly reloading is slow.

Second, no parallelism. One core does all the work while others sit idle.

Feste includes both approaches and chooses automatically. Matrices with fewer than 1,000 total multiply-add operations use the simple version shown above. The parallel overhead would cost more than the speedup gains. Larger matrices switch to a parallel cache-blocked algorithm that addresses both problems.

Cache Blocking

Cache blocking divides the work into small tiles that fit in L1 cache. We use 8×8 tiles, which is 64 floats or 256 bytes per tile. L1 cache is typically 32-64KB per core, so multiple tiles fit comfortably.

The algorithm divides both output and input matrices into 8×8 blocks. Here's the core loop for each block:

for i in block_start..block_end {

for k in k_block_start..k_block_end {

let a_val = A[i, k];

for j in j_block_start..j_block_end {

C[i, j] += a_val * B[k, j];

}

}

}Notice the innermost loop is over j. This accesses B sequentially by walking along a row. The CPU loads a cache line (typically 64 bytes or 16 floats) and uses all of it before moving to the next. The simple version jumped around memory as k changed, constantly loading new cache lines. The blocked version processes small regions repeatedly, so those cache lines stay hot. Cache hit rate goes way up.

Parallelization

We parallelize over output row blocks using Rayon:

result.par_chunks_mut(BLOCK_SIZE * n)

.enumerate()

.for_each(|(block_i, result_block)| {

// Each thread computes BLOCK_SIZE rows independently

});This splits the result matrix into chunks. BLOCK_SIZE is 8 (our tile size), and n is the number of columns in the result. So BLOCK_SIZE * n means we're giving each thread 8 complete rows to compute.

Rayon decides how many threads to use based on your CPU. It typically creates one thread per available core. On an 8-core machine, Rayon might spawn 8 threads and distribute the row blocks among them. One thread gets rows 0-7, another gets rows 8-15, and so on. Rayon handles all the scheduling automatically. We just tell it to "process these chunks in parallel" and it figures out the details.

Each thread works on different rows, so they never write to the same memory locations. No locks or synchronization needed. This is why matrix multiplication parallelizes so well.

Why Not Always Use the Optimized Version?

Parallelization has overhead. Rayon needs to split work across threads, schedule them, and manage synchronization. For a 2×2 matrix (16 operations total), that overhead costs more than just doing the work sequentially.

The blocking algorithm also has overhead. Dividing matrices into blocks and handling edge cases adds complexity. For tiny matrices that fit in cache already, the extra bookkeeping wastes time.

We benchmarked and found the breakeven around 1,000 multiply-add operations. Below that, the simple three-loop version wins. Above that, the optimized version wins. On a modern CPU, the optimized version gives roughly 2-4x speedup for large matrices. Not 8x on an 8-core machine because memory bandwidth is the bottleneck. All cores compete for RAM, and RAM can only deliver data so fast.

Batched Matrix Multiplication

Sometimes we need to do many matrix multiplications at once, all with the same structure but different data. Think of processing multiple sentences simultaneously, where each sentence needs the same calculations applied independently.

This creates 4D tensors where we need separate matrix multiplications for different combinations. Our implementation handles this by parallelizing across those independent calculations:

result.par_chunks_mut(seq1 * seq2)

.enumerate()

.for_each(|(bh_idx, chunk)| {

let b = bh_idx / n_heads;

let h = bh_idx % n_heads;

// Compute 2D matmul for this batch/head

}

);When we build the transformer in Part 3, you'll see this used for attention heads. Each attention head looks at the input differently, focusing on different patterns. They all run the same matrix multiplication operations, just with different learned weights. Processing them in parallel is a natural fit.

SIMD Auto-Vectorization Through Iterator Patterns

After we got the parallel blocked version working, profiling revealed another bottleneck in the innermost loop. We were using index-based access, and the compiler wasn't generating SIMD code. The fix was subtle: restructure the loop to use Rust's iterator pattern instead of index arithmetic.

// Before: Index-based access

for j in j_start..j_end {

let b_val = other.data[k_idx * n + j];

result_block[row_offset + j] += a_val * b_val;

}

// After: Iterator pattern

let b_slice = &other.data[k_idx * n + j_start..k_idx * n + j_end];

let result_slice = &mut result_block[row_offset + j_start..row_offset + j_end];

for (r, &b_val) in result_slice.iter_mut().zip(b_slice.iter()) {

*r += a_val * b_val;

}The code does exactly the same thing, but the compiler can now see what's happening. With iterators, LLVM recognizes the access pattern as something it can vectorize. It generates SIMD instructions that process multiple floats at once instead of one at a time.

The beautiful part is that the same Rust source compiles to the right SIMD instructions for whatever you're running on. ARM NEON on Apple Silicon, SSE2 on baseline x86, AVX2 on modern Intel and AMD. The compiler figures it out without any architecture-specific code in Feste itself.

Real testing showed this optimization cuts training time roughly in half on typical models. A model with more transformer layers sees bigger gains than one with fewer layers and larger embeddings, but either way you're looking at weeks saved per training run.

Softmax and Numerical Stability

When predicting the next token, the model produces scores for every token in the vocabulary. Higher scores mean higher confidence. But a score of 5.2 versus 4.8 doesn't tell you how much more likely one is than the other. Softmax converts these scores into percentages that sum to 100%.

Say the model reads "I love eating" and predicts what comes next. It might give "apples" a score of 2.0, "oranges" a score of 1.0, and "furniture" a score of 0.1. Softmax turns those into probabilities: about 66% for "apples", 24% for "oranges", 10% for "furniture".

The math uses the exponential function (exp). You might remember "e" from math class, the constant about 2.718. Raising e to a power is the exponential function, written as exp(x). A key property: larger inputs produce dramatically larger outputs. exp(2) is about 7.4, while exp(10) is about 22,000.

For our three scores [2.0, 1.0, 0.1]: exp(2.0) is 7.39, exp(1.0) is 2.72, exp(0.1) is 1.11. Sum those to get 11.22. Divide each by the sum: 7.39/11.22 is 0.66 (66%), 2.72/11.22 is 0.24 (24%), 1.11/11.22 is 0.10 (10%).

In reality, the model does this for every token in the vocabulary. A vocabulary of 20,000 tokens means 20,000 softmax scores that all sum to 100%. The model picks from all of them, though typically we only care about the highest-scoring options.

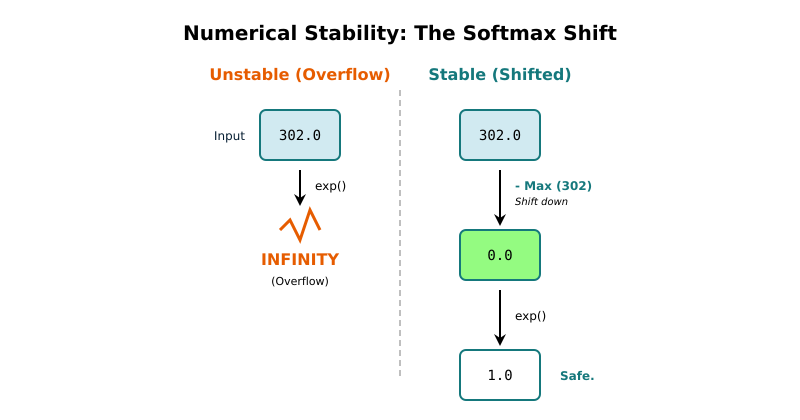

The Overflow Problem

This breaks when scores get large. Try computing exp(300.0) on a computer. You get infinity. The exponential function grows so fast that large numbers overflow the limits of floating-point representation.

Language models regularly produce scores in the hundreds. A direct softmax implementation would overflow immediately.

The Fix

We solve the overflow problem by subtracting the maximum score from all scores before computing exponentials:

let max =row.iter().fold(f32::NEG_INFINITY, |a, &b| a.max(b));

let exp_values: Vec = row.iter().map(|&x| (x -max).exp()).collect();

let sum: f32 = exp_values.iter().sum();

let normalized: Vec = exp_values.iter().map(|&x| x /sum).collect();First find the maximum value. Then subtract it from every score before computing exponentials. Finally, divide by the sum to get percentages.

Back to our example with scores [2.0, 1.0, 0.1] for "apples", "oranges", and "furniture". The maximum is 2.0. Subtract it from each score and we get [0.0, -1.0, -1.9]. Now compute exponentials: exp(0.0) equals 1.00, exp(-1.0) equals 0.37, exp(-1.9) equals 0.15. Sum those to get 1.52. Divide each by 1.52 and we get 0.66, 0.24, and 0.10. The same percentages as before.

Even if the original scores were huge like [302.0, 301.0, 300.1], subtracting the maximum (302.0) gives[0.0, -1.0, -1.9]. Small numbers that won't overflow. The exponentials work fine, and we get the same relative percentages.

This works because the largest exponential is always exp(0) = 1.0, and all others are smaller. No overflow. Large negative numbers like exp(-301.9) are just tiny numbers close to zero, which computers represent fine. It's large positive exponentials like exp(302.0) that overflow.

Subtracting the same value from all inputs before exponentials keeps the relative proportions identical. The percentages stay unchanged. They are numerically stable, and mathematically equivalent.

We compute softmax per row in parallel since each row is independent. Rayon distributes the work across cores automatically.

Broadcasting

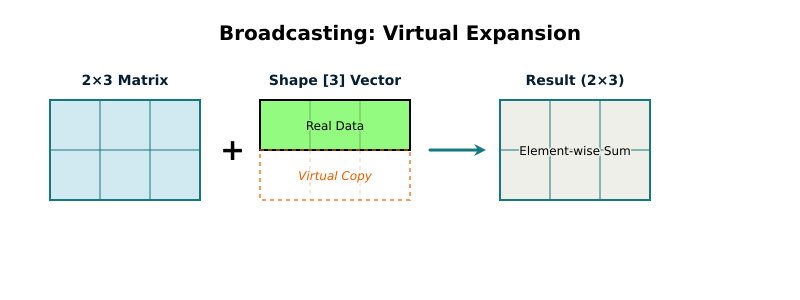

When you add two tensors together, they normally need the same shape. A 2×3 matrix plus another 2×3 matrix makes sense. But what if you want to add a single row of values to every row in a matrix?

Say you have a 2×3 matrix (remember, shape [2, 3] means 2 rows and 3 columns):

[1.0 2.0 3.0]

[4.0 5.0 6.0]

You want to add the values [0.1, 0.2, 0.3] to every row. In neural networks, these adjustment values are called biases. Without broadcasting, you'd duplicate them into a full 2×3 matrix before adding. That wastes memory and time.

Broadcasting does this automatically. Add a [3] vector to a [2, 3] matrix and the implementation figures out you mean "add this to each row" and does it directly without copies.

let matrix = Tensor::new(vec![1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0], vec![2, 3]);

let bias = Tensor::new(vec![0.1, 0.2, 0.3], vec![3]);

let result = matrix.add(&bias);The result is [2, 3] with the bias added to each row efficiently in both memory and speed.

This pattern appears constantly in neural networks. When a layer transforms its input, it multiplies by a weight matrix and then adds a bias. The bias is one value per output dimension, but you're processing many inputs at once. Instead of duplicating the bias for each input, broadcasting adds it efficiently. The same pattern appears in normalization layers, embedding layers, and various other operations throughout the model.

We also handle batch broadcasting. When processing multiple examples at once, you often want to apply the same operation to each one. A [4, 2, 3] tensor represents 4 batch items, each with shape [2, 3]. Broadcasting lets you add a single [2, 3] tensor to all 4 batch items.

Tensor libraries like NumPy support broadcasting across arbitrary dimension combinations with complex rules. Feste implements only what it needs: adding vectors to matrix rows, and applying operations across batches.

Element-wise Operations

Some operations work position by position. Add two tensors, you take the value at position [0,0] from the first tensor and add it to the value at position [0,0] from the second. Then [0,1] plus [0,1]. Then [0,2] plus [0,2]. And so on through the entire tensor.

For example, adding these two tensors:

[1.0 2.0 3.0] [0.1 0.2 0.3] [1.1 2.2 3.3]

[4.0 5.0 6.0] + [0.4 0.5 0.6] = [4.4 5.5 6.6]

Each position in the result comes from adding the corresponding positions in the inputs. We call these element-wise operations because they operate on elements independently. The calculation at one position doesn't affect any other position.

Multiplication, subtraction, and division work the same way. Take corresponding positions from both inputs, perform the operation, store the result. These operations appear everywhere in the model. Combining features from different layers. Applying activation functions. Scaling values.

Our implementation parallelizes all of these using Rayon:

pub fn add(&self, other: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

if self.shape == other.shape {

let result = self.data.par_iter()

.zip(&other.data)

.map(|(a, b)| a + b)

.collect();

return Tensor::new(result, self.shape.clone());

}

// Broadcasting cases...

}The par_iter() tells Rayon to process elements in parallel. It splits the data across threads, each thread processes its chunk, and the results get collected into a new vector. Multiplication, subtraction, and division follow the same pattern.

Scalar operations work similarly. Sometimes you need to multiply every element by the same value:

pub fn mul_scalar(&self, scalar: f32) -> Tensor {

let result = self.data.par_iter().map(|&x| x * scalar).collect();

Tensor::new(result, self.shape.clone())

}Every element gets multiplied by the scalar in parallel. For large tensors with thousands or millions of elements, parallelism provides significant speedup. For tiny tensors with dozens of elements, the threading overhead costs more than it saves. Rayon looks at the workload size and decides whether spawning threads is worthwhile or if sequential processing would be faster. Unlike matrix multiplication where we had to implement cache blocking ourselves, element-wise operations are simple enough that Rayon handles the optimization decisions for us.

Reshaping and Transposing

Reshaping reinterprets the same data with different dimensions. The actual numbers don't move or change, you just tell the tensor to organize them differently.

Take six values stored as [1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0]. You could interpret this as a 2×3 matrix:

[1.0 2.0 3.0]

[4.0 5.0 6.0]

Or as a 3×2 matrix:

[1.0 2.0]

[3.0 4.0]

[5.0 6.0]

They are the same six numbers in the same order in memory. Just different shapes. The code looks like this:

let matrix = Tensor::new(vec![1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0], vec![2, 3]);

let reshaped = matrix.reshape(&[3, 2]);The total number of elements must stay the same. You can't reshape 6 values into a 2×4 matrix because that would need 8 values. The model uses reshape when it needs data in a different arrangement for an operation. It can be used to flatten a multi-dimensional tensor into a vector before a linear layer, or to split or merge dimensions for attention heads.

Transposing is different. It actually rearranges the data:

let matrix = Tensor::new(vec![1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0], vec![2, 2]);

let transposed = matrix.transpose(0, 1);For a 2×2 matrix like:

[1.0 2.0]

[3.0 4.0]

Transpose swaps rows and columns to get:

[1.0 3.0]

[2.0 4.0]

The data actually moves. Position [0,1] becomes position [1,0]. This is the standard matrix transpose from linear algebra.

For higher dimensional tensors, transpose can swap any two dimensions. You specify which two dimensions to swap and it rearranges the data accordingly. Transformers use this when computing attention. The details of how and why will become clear in Part 3 when we build the model architecture. For now, just know that transpose is a fundamental operation we need.

Statistical Operations

Neural networks work better when data stays in a reasonable numeric range. If values get too large or too small, training becomes unstable. Layer normalization is a technique that keeps values centered and scaled appropriately.

The math requires computing the mean (average) and variance (spread) of values. Say you have a row of numbers [1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0]. The mean is 3.0 (add them up and divide by 5). The variance measures how spread out the values are from that average. Values close to the mean give low variance. Values far from the mean give high variance.

We need to compute these statistics along specific dimensions of a tensor. Say you have a 2×3 matrix:

[1.0 2.0 3.0]

[4.0 5.0 6.0]

You might want the mean of each row separately. Row 1 averages to 2.0, row 2 averages to 5.0:

let mean = tensor.mean(-1, true);The -1 tells it which direction to compute. For a 2×3 matrix, -1 means "work across each row." So we get one mean per row. If we used 0 instead, it would work down each column, giving us one mean per column.

The true tells it to keep the result as a matrix instead of flattening to a simple list. Getting [[2.0], [5.0]] (a 2×1 matrix) instead of [2.0, 5.0] (a flat list) makes broadcasting work automatically when we use these means in the next calculation.

Variance works the same way, computing how spread out the values are in each row:

let var = tensor.var(-1, true);The implementation splits the tensor into slices along the target dimension, computes statistics for each slice in parallel, then collects the results.

Layer normalization uses these statistics to standardize values. Using our 2×3 matrix example:

let mean = x.mean(-1, true); // [[2.0], [5.0]]

let var = x.var(-1, true); // variance for each row

let normalized = x.sub(&mean).div(&var.add_scalar(eps).sqrt());

let scaled = normalized.mul(&gamma).add(&beta);First subtract the mean from every value in each row. Row 1 becomes [-1.0, 0.0, 1.0] (centered around zero). Then divide by the standard deviation (square root of variance). We add a tiny value (commonly called epsilon and written as eps in our code) to the variance before taking the square root so we never divide by zero if all the values in a row happen to be identical. The value is typically something tiny like 0.00001. Now the values have a consistent spread.

At this point all the values are standardized, but forcing everything to have mean 0 and variance 1 might be too restrictive. So we add two more steps. Scale by multiplying with gamma (one learned value per dimension). Shift by adding beta (another learned value per dimension). These are parameters the model learns during training, letting it decide how much normalization is actually helpful. If gamma is 2.0 and beta is 1.0, values get doubled and then shifted up by 1. The model figures out the best values for these parameters.

The details of why this helps training will make more sense in Part 3 when we build the transformer layers. For now, know that we can compute statistics along tensor dimensions and use them to normalize data.

Masked Fill

When predicting the next token, the model shouldn't be able to peek at future tokens. That would be cheating. If the model is trying to predict what comes after "To be or", it should only see those three tokens, not the rest of the sentence.

Feste enforces this with masking. Before the model processes attention scores, we replace certain positions with negative infinity:

let scores = query.matmul(&key_transposed);

let masked = scores.masked_fill(&mask, f32::NEG_INFINITY);

let attention = masked.softmax(-1);The mask is a grid of 0s and 1s. Where the mask is 1, we replace that score with negative infinity. Remember from softmax that exp(-infinity) = 0. So after softmax, those positions contribute nothing. The model effectively can't see them.

For predicting the next token, we use a causal mask (also called an upper triangular mask):

[0 1 1]

[0 0 1]

[0 0 0]

Position 0 can only look at itself (everything else is masked with 1s). Position 1 can look at positions 0 and 1 (position 2 is masked). Position 2 can look at all previous positions (nothing is masked). Each position only sees tokens that came before it, never tokens that come after.

The details of how attention works and why masking matters will become clear in Part 3. For now, just know we can selectively block the model from seeing certain values.

Memory Layout and Performance

We store tensors as flat arrays. The shape tells us how to interpret them, and the strides tell us how to navigate them. For shape [2, 3, 4], the strides are [12, 4, 1].

Those strides are the number of positions to jump when you move one step along each dimension. Moving one step in dimension 0 (between "sheets" in our 3D cube) means jumping 12 positions. Moving one step in dimension 1 (down a row) means jumping 4. Moving one step in dimension 2 (across a column) means jumping 1.

The data sits in memory like this:

[a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x]

Shape [2, 3, 4] means 24 values interpreted as 2 sheets of 3 rows of 4 values each. Strides [12, 4, 1] tell us how to find any element.

This row-major layout means the last dimension is most tightly packed. Values next to each other in the last dimension sit next to each other in memory. When the CPU loads data, it grabs chunks of nearby values (cache lines). When accessing sequentially in the last dimension, every value is already loaded which is perfect cache efficiency.

Operations that jump around break this. Matrix multiplication accesses one matrix by fixing a column and walking through different rows. Each step jumps many positions. The CPU constantly loads new cache lines instead of reusing what's already loaded. This is why we needed cache blocking.

What We Haven't Implemented

Feste implements what GPT-2 needs. Beyond that, we made deliberate choices about what to skip.

Memory management is one area. Feste allocates new memory for every operation. When you add two tensors, you get a brand new chunk of memory with the result. PyTorch reuses buffers through memory pools to avoid repeatedly asking the operating system for memory. This requires complex bookkeeping and lifetime tracking. It matters for scale but not for correctness, so we skipped it.

GPU support is another. Feste runs on CPU cores. Modern training uses GPUs with thousands of cores working in parallel. But GPU programming is a different world entirely. You write kernels in CUDA, worry about memory coalescing, and optimize for warp-level parallelism. Adding GPU support would triple the codebase and teach GPU programming instead of transformers. We chose to stay CPU-only.

Automatic differentiation we're saving for later. Feste's tensors don't track gradients. Training requires derivatives so the model knows how to adjust its weights. Part 4 will add this, but it's substantial work involving computation graphs and backpropagation. We're building up to it rather than loading everything into Part 2.

We also didn't implement operations beyond what GPT-2 needs. PyTorch supports hundreds of operations for different architectures. It includes convolutions for computer vision, recurrent operations for sequence models, and specialized activations. Each new operation multiplies the testing surface and adds complexity. We implement the essential ones and nothing more.

Manual SIMD intrinsics are another skip. Modern CPUs have SIMD instructions that process multiple values at once. We structure our loops with iterator patterns to let the compiler auto-vectorize. Hand-tuned SIMD would be faster but less portable and harder to maintain. We get good enough performance across ARM, x86, and future architectures without it.

Sparse tensors didn't make the cut either. Most transformers use dense tensors where you store every element even if it's zero. Sparse tensors store only non-zero values with their positions, saving memory when data is mostly empty (and has nothing to do with sparse models like Mixture of Experts). This requires different algorithms and careful index management. GPT-2 doesn't need it.

Feste chooses simplicity over performance. The operations work correctly and run fast enough to train small models. You can experiment, understand what's happening, and see results. It's not built for training large models at scale, but that's not the goal. We're learning how transformers work from the ground up.

Running the Example

The example demonstrates every operation we've discussed: creating tensors, matrix multiplication, element-wise operations, broadcasting, softmax, reshaping, and masked fill. Run it with:

cargo run --release --example 02_tensor_operationsThere's nothing language-model specific yet. Just proof that our tensor operations work. You'll see a 2×3 matrix created from six values. A 64×64 matrix multiplication that completes in under a millisecond on an M1 MacBook Pro, showing the parallelization works. Softmax with extreme logits like [100.0, 200.0, 300.0] that would overflow without our max subtraction trick, but produce valid probabilities [0.0, 0.0, 1.0] that sum to 1.0. Broadcasting that adds a 3-element bias vector to each row of a 2×3 matrix without wasting memory. Masked fill that sets future positions to negative infinity so they disappear after softmax.

Everything runs quickly, fast enough to iterate and clear enough to understand. The foundation is solid.

What's Next

Now that we know what tensors are and how to work with them, it's time to assemble a transformer architecture.

A transformer takes tokens in and passes them through a series of stacked layers. Each layer looks at all the tokens together and adjusts their representations based on context. After all the layers, you have a refined representation that becomes your prediction of what tokens will come next.

In Part 3, we'll build this architecture. We'll use random weights, so predictions will be nonsense. But the structure will be complete. Feed it "To be or not to be" and it produces scores for every token in the vocabulary. This is the foundation. Once we add training in a later part, we'll see if we can teach it to predict Shakespeare.