How-to Guide

Part 3: Model Architecture, Building an LLM from Scratch in Rust

January 12, 2026

We're implementing GPT-2, as OpenAI released in 2019. It proved you could build a language model that generates coherent text by predicting one token at a time based on everything that came before it. They published the paper openly and everything built since is basically a variation on this architecture. Feste implements it from scratch in Rust.

The conceptual pieces we're building are embeddings, attention mechanisms, layer normalization, residual connections, and feedforward networks. Each one solves a specific problem in the flow of information through the model. Attention is the most important one. Everything else exists to support it or make it work better.

What is a Transformer?

The transformer is the architecture that powers modern language models. The name comes from how it transforms input sequences into output predictions through a series of learned operations. The architecture predicts the next token given previous tokens, though our untrained model will produce meaningless predictions until we teach it patterns from actual text.

Before transformers, language models used recurrent neural networks (RNN). RNNs processed text sequentially, one token at a time, always waiting for the previous step to complete before moving to the next. The model struggles to learn dependencies between distant tokens. When predicting what comes after "better a witty fool than a foolish", the model needs "fool" to influence its understanding of "foolish" several positions later. RNNs can theoretically do this, but in practice the sequential nature makes learning those long-range patterns extremely hard.

Transformers ditched sequencing. All tokens process in parallel, and attention lets each token look at any other token directly. Position 7 can reference position 2 without going through 3, 4, 5, and 6. This parallelization maps perfectly to modern hardware and makes training orders of magnitude faster. More importantly, it works for long sequences. GPT-2 handles 1,024 tokens at once. GPT-4 handles over 128,000 tokens. The attention mechanism maintains coherence across that entire range.

The architecture stacks two kinds of layers. Attention layers let tokens communicate across the sequence. Feedforward layers process what the attention layer found. GPT-2 uses 12 of these blocks stacked together. Each block refines the representations. Patterns learned early propagate through later layers and build into more abstract understanding.

The Forward Pass

The model takes a sequence of tokens and processes them through all these layers to produce a list of scores, one for each token in the vocabulary. These scores tell you which tokens are likely to come next based on what's come before. Pick the highest scoring token, or sample from the top candidates. Feed that token back in as the next input and repeat. That's how language generation works.

Everything we're about to explain, including embeddings, attention, layer normalization, residual connections, and feedforward networks, exists to compute those final scores efficiently and accurately.

For now we're implementing the forward pass, the inference direction where the model takes input tokens and produces output predictions. Training comes later and requires the backward pass, where gradients flow backwards through every operation so the model can learn which weights work better. You need a working forward pass before backpropagation makes sense. More fundamentally, understanding how the model makes predictions comes before understanding how it learns to make better predictions.

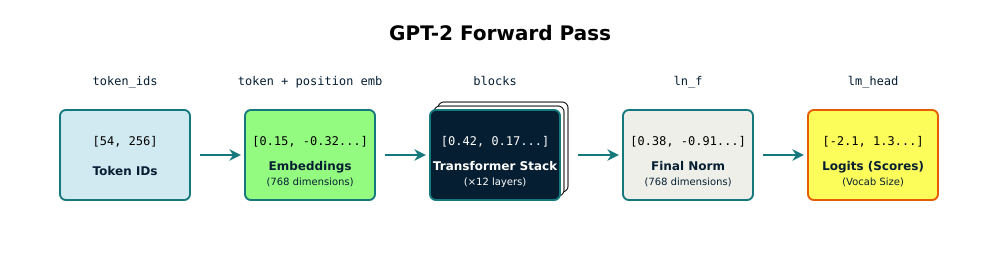

The forward pass in Feste flows through multiple stages. Token IDs enter as integers. Token and position embeddings convert them to 768-dimensional vectors. These vectors flow through 12 transformer layers that refine the representations. A final layer normalization keeps values stable. Then a projection back to vocabulary space produces one score per token, one for each of the 50,257 possible next tokens.

And that's it, the entire flow. Token IDs in, vocabulary logits out. The interesting part is what happens in those transformer layers. Each layer uses attention to let tokens look at each other and decide what matters, then uses feedforward networks to process that information. The layers stack together, each refining what the previous layer learned.

We'll build this piece by piece, but the overall shape is simple. Something goes in, it gets transformed, and something comes out.

Embeddings: From IDs to Vectors

Token IDs are just integers. The tokenizer gave us [54, 256, 65] for "To be". But neural networks don't work with raw integers. They need richer representations to work with. Embeddings solve this by converting each token ID into a vector of numbers. GPT-2 uses 768-dimensional embeddings, so token 54 becomes a vector of 768 floating point values instead of just the number 54.

The embedding lookup is straightforward. We maintain a matrix of shape [vocab_size, 768]. Each row corresponds to one token ID. Token 54's embedding is row 54. Token 256's embedding is row 256. Looking up an embedding means finding the right row and copying those 768 floating point numbers.

The values in this embedding matrix start as random numbers, which is why untrained models produce garbage. During training, these values get adjusted based on which tokens predict which other tokens well. The model learns that tokens appearing in similar contexts should have similar embeddings. "King" and "queen" both commonly follow "the" and precede words like "ruled", so they end up close together in this 768-dimensional space. The model discovers this structure automatically.

For a vocabulary of 50,000 tokens with 768 dimensions, the embedding matrix holds 38 million parameters. That's just one component of the model, and it's already massive.

The implementation is simple indexing:

pub struct Embedding {

pub weight: Tensor,

}

impl Embedding {

pub fn forward(&self, token_ids: &[Vec<usize>]) -> Tensor {

// For each token ID, copy its embedding vector

let mut output = Vec::with_capacity(batch_size * seq_len * n_embd);

for batch in token_ids {

for &token_id in batch {

let start = token_id * n_embd;

let end = start + n_embd;

output.extend_from_slice(&self.weight.data[start..end]);

}

}

Tensor::new(output, vec![batch_size, seq_len, n_embd])

}

}For each token ID, we slice out the corresponding row from the weight matrix and add it to the output. Do this for every token in the sequence and you've converted integers into 768-dimensional vectors that the rest of the network can work with.

Position Embeddings

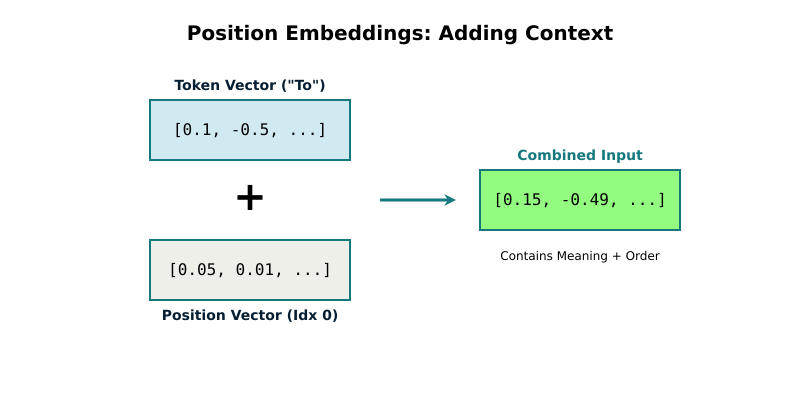

Transformers process all tokens in parallel. This is great for speed but creates a problem: the model sees "To be or not to be" but has no idea that "To" comes before "be". Order information is completely lost.

Position embeddings fix this elegantly. We maintain a second embedding table, separate from the token embeddings. This table has one row per position in the sequence instead of one row per token. The block_size in the config determines how many position embeddings we need. GPT-2 uses a block_size of 1,024, meaning we have position embeddings for positions 0 through 1,023. Each position embedding is 768 numbers, the same size as token embeddings. This means we can add them together element-wise.

When processing "To" at position 0, we look up two vectors and add them. The token embedding for "To" defines what this token means. The position embedding for position 0 contributes information about what it means to be the first in the sequence. The sum captures both pieces of information at once.

Token embedding: [0.1, -0.3, 0.2, ...] (768 numbers)

Position embedding: [0.05, -0.02, 0.01, ...] (768 numbers)

Combined: [0.15, -0.32, 0.21, ...] (768 numbers)During training, the model learns position embeddings that encode useful information about sequence positions. Position 0 embeddings might cluster patterns that commonly appear at the start of sentences. Position 2 might learn patterns that follow verbs. The model discovers these patterns automatically from data.

For "To be or not to be", we combine six token embeddings with position embeddings 0 through 5. If text is longer than the block_size, the model can't process it in a single forward pass. You either truncate the input or process it in overlapping chunks.

This block_size limit is what you know as the context window in ChatGPT or Claude. When someone says a model has a 200,000 token context window, they mean the block_size is 200,000. The mechanism is identical no matter the size. It's a hard limit on how much history the model can see at once.

Layer Normalization

Deep neural networks are unstable when you stack many layers. Values can explode to huge numbers or shrink toward zero as they flow through the transformations. This makes training difficult or impossible.

Layer normalization keeps values in a reasonable range. For each token's 768-dimensional vector, we compute its mean and variance, then rescale it so the mean becomes zero and variance becomes one. This standardization prevents the explosive growth or shrinkage that destabilizes training.

output = ((input - mean) / sqrt(variance + eps)) × gamma + betaThe formula looks mechanical, but gamma and beta are learned parameters that give the model flexibility. After standardizing to a mean of zero and a variance of one, we multiply by gamma and add beta. The model learns what values work best during training. Sometimes it keeps gamma near 1 and beta near 0, letting the standard normalization do its job. Other times it adjusts these values. This flexibility means we get the stabilizing effect of normalization without forcing an inflexible configuration.

The eps term prevents division by zero. It's a tiny constant, typically 0.00001. If all values in a token's vector happen to be identical, variance would be zero. Adding eps before taking the square root keeps the computation stable without meaningfully affecting the result when variance is normal.

Layer normalization appears twice per transformer layer. Once before attention and once before the feedforward network. Each normalization step has its own learned gamma and beta parameters. Different parts of the network learn different normalizations, but all tokens passing through the same normalization step share the same gamma and beta.

pub fn forward(&self, x: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

let mean = x.mean(-1, true);

let variance = x.var(-1, true);

let normalized = x.sub(&mean).div(&variance.add_scalar(self.eps).sqrt());

normalized.mul(&self.gamma).add(&self.beta)

}The code directly implements the formula. First compute mean and variance across each token's 768 values, then subtract the mean, divide by the standard deviation, and finally scale by gamma and shift by beta.

Multi-Head Self-Attention

Attention is the breakthrough that makes transformers work. It lets each position in the sequence look at every other position and decide what's relevant. Before attention, models processed text sequentially and couldn't see multiple parts of the input at once. This mechanism is why transformers can maintain coherence across tens of thousands of tokens and train efficiently on massive datasets.

Attention operates on the combined token and position embeddings we just built. Each token's vector already contains both its meaning and its location in the sequence when it enters the attention mechanism.

The mechanism works like this. For each token position, we compute three vectors by multiplying the token's embedding through learned weight matrices. Query, Key, and Value are 64-dimensional vectors (in GPT-2 with 12 heads). The Query represents what information this token is looking for. The Key represents what this token can offer. The Value is the actual content this token contributes. We compare each Query to all the Keys to compute relevance scores. Then we use those scores to take a weighted average of all the Values.

The learned weight matrices are what enable the model to develop useful attention patterns. During training, the model adjusts these weight matrices so that Query and Key vectors from related tokens end up pointing in similar directions. When "foolish" needs to understand word contrast, its Query vector points toward similarities with other contrast-related patterns. "Fool" earlier in the sequence has a Key vector that points in that same direction because it's related to wordplay and comparison. When you compute the dot product between these vectors, you get a high score. Structural words like "a" and "than" have Query and Key vectors that don't align with contrast patterns, so their scores stay low. The model learns which patterns matter through training, adjusting the weight matrices until the right words attend to each other.

The math is elegant. We compute attention scores by taking the dot product of each Query with all Keys:

The formula that captures this is:

Attention(Q, K, V) = softmax(Q @ K^T / sqrt(d)) @ VThe dot product measures how similar two vectors are. A high score means they point in similar directions. We scale by dividing by sqrt(d) where d is the dimension per head (64 in our case). This scaling prevents scores from getting too large, which would make softmax produce overconfident probabilities. After softmax, the scores become probabilities that sum to one. We use these probabilities to take a weighted average of all the Values. The result is a new representation for each token that incorporates information from positions it deemed relevant.

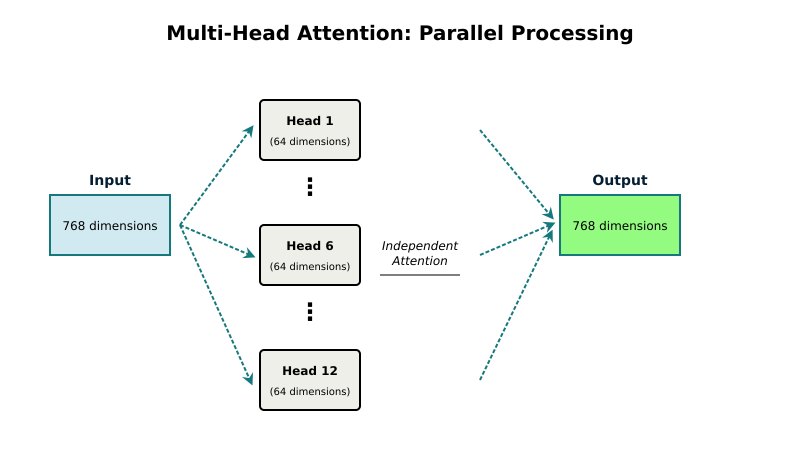

Multi-Head Attention

Running attention multiple times with different learned transformations lets the model focus on different aspects of the sequence simultaneously. One head might learn local patterns, matching nearby tokens. Another might learn long-range dependencies, like "fool" relating to "foolish" several positions later. A third might focus on syntactic relationships like adjective-noun pairs. By running all these heads in parallel, the model can attend to many relationship types at once.

GPT-2 uses 12 attention heads. The 768-dimensional embeddings get split across them, giving each head 64 dimensions to work with. All 12 heads compute their own Query, Key, and Value vectors and run the attention mechanism in parallel on their own slice of the data.

The Implementation

Here's how it works in code:

pub fn forward(&self, x: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

// 1. Project to Q, K, V (one big matrix multiply, then split)

let qkv = self.c_attn.forward(x);

let (q, k, v) = qkv.split_into_thirds();

// 2. Split into heads

let q = self.split_heads(&q);

let k = self.split_heads(&k);

let v = self.split_heads(&v);

// 3. Compute attention scores

let scores = q.matmul(&k.transpose(2, 3));

let scores = scores.mul_scalar(1.0 / (self.head_dim as f32).sqrt());

// 4. Apply causal mask (created for this sequence length)

let mask = self.create_causal_mask(seq_len);

let scores = scores.masked_fill(&mask, f32::NEG_INFINITY);

// 5. Softmax and apply to values

let attn = scores.softmax(-1);

let out = attn.matmul(&v);

// 6. Merge heads and project

let out = self.merge_heads(&out);

self.c_proj.forward(&out)

}Step 1 computes Q, K, and V by multiplying the input through three learned weight matrices, all done efficiently in one big matrix multiplication. Step 2 reshapes the 768 dimensions into 12 heads of 64 dimensions each, so each head works independently. Step 3 computes attention scores by multiplying each Query by all Keys transposed, then scales by sqrt(head_dim). Step 4 applies the causal mask, which we'll explain next. Step 5 applies softmax to convert scores into probabilities, then multiplies by the Values to get a weighted average. Step 6 recombines the 12 heads back into a single 768-dimensional vector and applies a final learned transformation to mix information from all the heads.

The causal mask prevents tokens from looking at future positions, which maintains the language modeling constraint that you can only predict the next token based on the past.

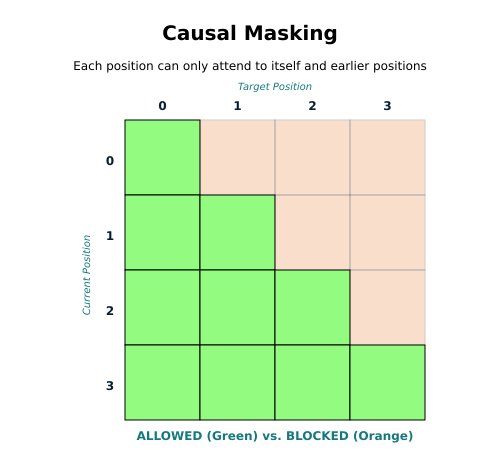

Causal Masking

Language modeling predicts the next token given previous tokens. When processing "better a witty fool than", position 4 uses positions 0 through 4 to predict what comes next. It cannot see future positions. That would let the model cheat by looking ahead.

Causal masking prevents this. Before computing attention, we apply a mask that blocks future positions. The mask is a triangular matrix where the upper triangle contains 1s and the lower triangle contains 0s:

[0 1 1 1]

[0 0 1 1]

[0 0 0 1]

[0 0 0 0]

Where the mask is 1, we replace the attention score with negative infinity. After softmax, exp(-inf) = 0, so masked positions contribute nothing. Position 0 only sees itself. Position 1 sees positions 0 and 1. Position 2 sees 0, 1, and 2. This triangular pattern ensures each position only attends to the past, never the future.

The MLP Layer

After attention decides what to focus on, the MLP processes that information. MLP stands for multi-layer perceptron. The name makes it sound complicated, but it's just two matrix multiplications with an activation function in between.

The structure is simple. We expand the 768-dimensional embeddings to 3,072 dimensions (a 4x expansion), apply an activation function called Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU), then project back to 768 dimensions. The expansion creates space for complex transformations. The activation function matters because pure matrix multiplication is limited. If you only multiply and add numbers, you get linear relationships, output is always proportional to input. A number twice as large gives you a result twice as large. You can't learn complex patterns that way. GELU applies a different rule. Small positive numbers get through mostly unchanged. Large positive numbers stay large. Negative numbers get pushed toward zero. This rule is not proportional, it doesn't scale linearly. That variable behavior is what lets the network learn more sophisticated relationships. The expansion gives GELU more dimensions to work with, more room to express the complex ideas before squashing back down.

Why 4x expansion? Empirically it works well. The original Transformer paper used this ratio and it's stuck as the standard. The expansion provides capacity for complex transformations while keeping the main pathway through the network (the residual stream) relatively efficient.

GELU, Gaussian Error Linear Unit, is the activation function we use. For positive numbers, it mostly leaves them alone. For negative numbers, it smoothly reduces them toward zero instead of cutting them off abruptly. The smooth behavior works better in practice than sharp cutoffs.

pub fn gelu(x: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

let sqrt_2_over_pi = (2.0_f32 / std::f32::consts::PI).sqrt();

let coeff = 0.044715_f32;

let result: Vec<f32> = x.data.iter().map(|&val| {

let x_cubed = val * val * val;

let inner = sqrt_2_over_pi * (val + coeff * x_cubed);

0.5 * val * (1.0 + inner.tanh())

}).collect();

Tensor::new(result, x.shape.clone())

}The code applies GELU to every element in the tensor. The constants sqrt(2/pi) and 0.044715 define GELU's specific curve, making this particular smooth function work the way it does. The formula computes that curve and applies it element-wise to every value. The exact mathematical derivation of those constants isn't critical for understanding how transformers work, but they're baked into GELU's definition.

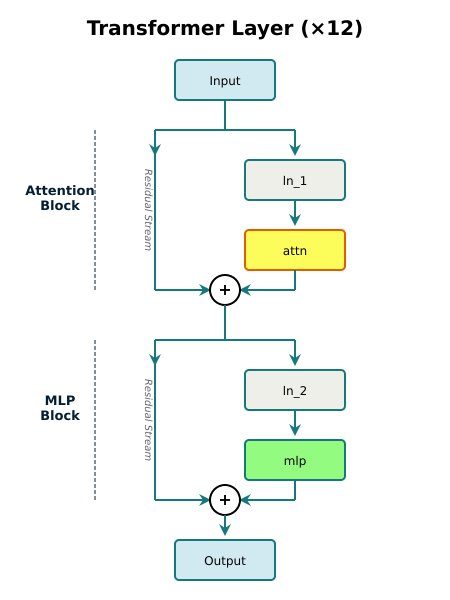

Transformer Layers

A transformer layer combines attention and MLP with residual connections. A residual connection means the original input bypasses the transformation and gets added back to the output. This creates multiple pathways for information to flow through the network.

The layer has two residual blocks. First, normalize the input and run it through attention, then add the original input back. Second, normalize that result and run it through the MLP, then add the original input back. The data flows through the transformations while simultaneously bypassing them.

Why does this matter? Without residual connections, information can get blocked. A layer that's still learning or poorly initialized could suppress the signal completely. With residual connections, information can always flow directly through the bypass path, letting gradients flow backwards during training and preventing information bottlenecks during inference.

pub fn forward(&self, x: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

// Step 1: Attention with residual connection

let x = x.add(&self.attn.forward(&self.ln_1.forward(x)));

// Step 2: MLP with residual connection

x.add(&self.mlp.forward(&self.ln_2.forward(&x)))

}The code directly maps to the architecture. Normalize and apply attention, then add the original input back. Do the same for the MLP, normalizing and applying the transformation, then adding the input back. This pattern repeats across all the transformer layers.

GPT-2 stacks 12 of these identical blocks. Each layer receives the output from the previous layer and refines it further. As information flows through the stack, different layers learn to extract different levels of abstraction from the tokens. The early layers tend to learn surface-level patterns like common word combinations and local relationships. Middle layers discover syntactic structures and grammatical patterns. Later layers learn more abstract semantic relationships and higher-level reasoning. The residual connections ensure that all this refined information can flow between layers without getting blocked or corrupted.

The Complete Model

Now we assemble all the pieces into the complete architecture. We've built embeddings that convert token IDs to vectors. We've built attention layers that let tokens look at each other and decide what matters. We've built feedforward networks that process that information. We've added layer normalization to keep values stable and residual connections to prevent information bottlenecks. All of that was building toward the complete model. The forward pass starts with token IDs. We convert them to token embeddings, add position embeddings so the model knows where each token sits in the sequence, and then feed everything through the 12 transformer layers. Each layer refines the representations. Patterns from earlier layers propagate through later layers and accumulate into more abstract understanding. After all 12 layers have done their work, we apply one final layer normalization to ensure values stay in a reasonable range. Then we project from 768 dimensions back to vocabulary space, producing a score for each of the 50,257 possible tokens.

pub fn forward(&self, token_ids: &[Vec<usize>]) -> Tensor {

let seq_len = token_ids[0].len();

// Token and position embeddings

let mut x = self.token_embedding.forward(token_ids);

let pos_emb = self.position_embedding.forward_range(0, seq_len);

x = x.add_broadcast(&pos_emb);

// Through all 12 transformer layers

for block in &self.blocks {

x = block.forward(&x);

}

// Final normalization and vocabulary projection

x = self.ln_f.forward(&x);

self.lm_head.forward(&x)

}The output has the shape [batch, seq_len, vocab_size]. For each position in the sequence, we get a score for every token in the vocabulary. These logits are raw unnormalized values. Feed the model "To be or not to be" and you get scores for what comes next. The weights are random so those scores are garbage, but the architecture is complete.

This is a full transformer. Token IDs flow through embeddings, through 12 layers of attention and feedforward processing, through final normalization, and out to vocabulary scores. During training, the model adjusts 87 million weights to make those scores point toward the right tokens. That's where the intelligence comes from. The architecture itself is just the mechanism that makes learning possible.

Model Sizes

Feste implements several configurations. Here's the configuration that matches the original GPT-2 Small architecture:

impl Config {

pub fn gpt2_small(vocab_size: usize) -> Self {

Self {

vocab_size,

n_embd: 768,

n_heads: 12,

n_layers: 12,

block_size: 1024,

dropout_rate: 0.1,

}

}

}That's 768-dimensional embeddings, 12 attention heads, 12 layers, and a 1024-token context window. With a smaller vocabulary for experimentation, this configuration uses about 87 million parameters.

Feste also includes smaller configurations for different purposes. The tiny configuration uses 64-dimensional embeddings across 2 layers with single-head attention for quick debugging runs. The small configuration uses 128 dimensions across 3 layers, also with single-head attention, balancing capability with speed. The medium configuration scales to 256 dimensions across 4 layers with 4 attention heads, demonstrating how the embedding dimension splits across heads to give each head 64 dimensions to work with.

Parameter counts matter because they directly affect training time and memory. The embeddings alone are expensive. For a 512-token vocabulary with 64-dimensional embeddings, that's already 65,536 parameters just for the token embedding table. Position embeddings add another 65,536. The way parameters grow depends on what you change. The attention and MLP matrices in each layer have sizes based on the embedding dimension. With 768-dimensional embeddings, those matrices are roughly 768 × 768 in size, which is 590,000 parameters per matrix. If you add more layers, you just multiply that by the number of layers. If you increase the embedding dimension, the matrices get bigger exponentially. With 256 dimensions, you'd have roughly 256 × 256 = 65,000 parameters per matrix. Double to 512 dimensions and you get 512 × 512 = 262,000 parameters per matrix. The relationship is quadratic.

This assumes we're counting just the weights. Forward passes also require memory for activations, which grows with how many sequences you process at once (batch size) and how long each sequence is (sequence length, up to your context window). Processing one sequence at a time takes much less memory than processing a dozen sequences in parallel.

Running the Example

The example creates a complete transformer and runs a forward pass:

cargo run --release --example 03_model_architectureIt builds a tiny model, counts its parameters broken down by component, and processes sample input through the entire architecture. You see tensor shapes at each stage: token IDs becoming embeddings, flowing through layers, and emerging as vocabulary logits. The logits themselves are random noise because the weights are untrained, but the shapes are correct and the architecture is complete.

On a modern laptop (M-series Mac), the tiny model completes a forward pass on 8 tokens in under 5 milliseconds. The small model takes about 10 milliseconds, the medium model around 28 milliseconds. These timings make experimentation practical. You can iterate quickly without waiting minutes for each forward pass.

What's Next

We've now built a complete GPT-2 architecture from first principles. Token IDs flow through embeddings, through 12 layers of attention and feedforward processing, and out to vocabulary logits. The weights are random, so predictions are garbage. But the structure is complete and correct.

The remaining challenge is the hardest part: training. The architecture you've built is just the mechanism. Now we have to make it learn. Part 4: Training Infrastructure, Building an LLM From Scratch in Rust implements training infrastructure. Backpropagation flows gradients backwards through every layer. An optimizer uses those gradients to update weights. A loss function measures how well the model predicts the next token. These pieces transform random weights into a working language model.

Part 5: A Witless Fool, Building an LLM From Scratch in Rust trains models on Shakespeare's complete works. You'll see how the model learns to predict tokens better and better as training progresses. You'll watch it learn Shakespeare's style, character names, and dramatic patterns. Our goal will be to leverage the architecture we've just built to generate coherent text that reads like it could have come from the Bard himself.