White Paper

Getting LLMs to Do What You Want: A Practical Guide to Prompt Engineering

November 24, 2025

Executive Summary

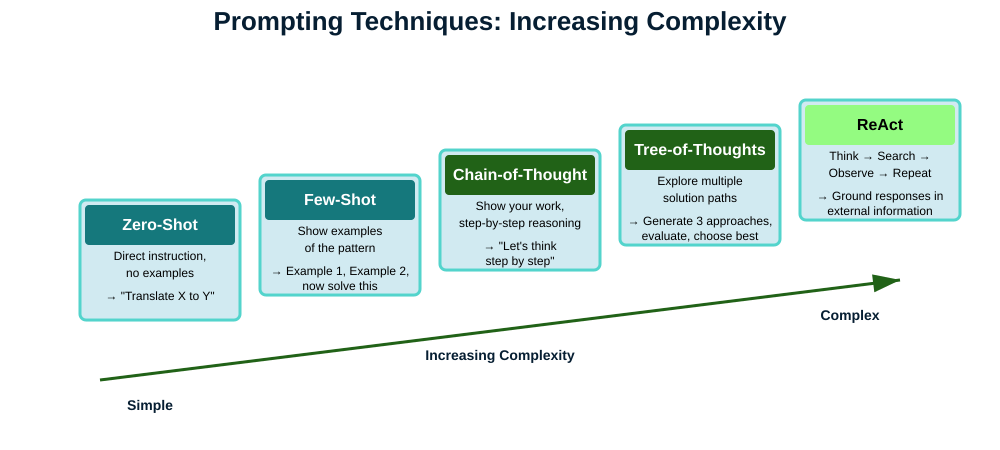

Prompt engineering is about learning to communicate clearly with LLMs, which take everything literally and confidently produce either nonsense or exactly what you need. This guide walks through practical techniques including zero-shot, few-shot, Chain-of-Thought, Tree-of-Thoughts, and ReAct, showing when and how to use them. It emphasizes being specific, structuring complex prompts, providing context, and iteratively refining instructions. By understanding that LLMs predict patterns rather than thinking, you can craft prompts that consistently get useful outputs, avoid common pitfalls, and make the most of these powerful but limited tools.

Introduction

Prompt engineering is learning how to clearly communicate with a system that takes everything literally. These sophisticated pattern-matching systems will confidently produce nonsense or exactly what you need, depending entirely on how you ask. When you understand that LLMs are predicting patterns rather than actually thinking, you can write prompts that get the job done faster and more effectively. Here's what works, what doesn't, and why.

Prompting Techniques: At a Glance

If you're here for a quick refresher or just need the essentials, here's what actually works:

Zero-Shot: Give a direct instruction, no examples needed. Works for common tasks.

Summarize this article in three sentences.Few-Shot: Provide examples to show the pattern you want. The model will continue that pattern in its responses.

Product: iPhone case

Category: Electronics

Product: Running shoes

Category: Footwear

Product: Bluetooth speaker

Category:

Chain-of-Thought: Make the model show its reasoning. Common triggers include "Let's think step by step," "Show your work," or "Walk me through your reasoning." You can also demonstrate the reasoning pattern you want with examples.

Question: [your problem]

Let's work through this step by step.

Tree-of-Thoughts: Explore multiple solutions before choosing. Good for decisions or strategy.

Generate three different approaches to [problem],

evaluate the pros and cons of each, and then recommend the best one.The basics come down to being specific instead of vague ("100-150 words" beats "fairly short"), structuring complex prompts with clear sections and delimiters, and recognizing that positive instructions work better than negative ones. When something isn't working, you either need to show examples or break the task into smaller steps. Start simple and refine based on what comes back.

This overview gets you operational, but there's a world of nuance in when to use each technique. For example, how to combine them effectively, why certain approaches fail with particular tasks, and how to debug when things go sideways. Understanding the mechanics behind these patterns is the difference between copying templates and actually engineering prompts that work. Let's start by understanding what a prompt really is and what makes one effective.

The Prompt as an Instruction Manual

Think of a prompt as a driving manual written for someone who knows how to operate every vehicle ever made but has no idea where you're trying to go or why. They have enough knowledge to navigate a complex roundabout in rush hour traffic or operate a forklift in a warehouse, but without clear instructions, they might end up doing donuts in the parking lot. You need to specify not just what to do, but how, why, and in what style.

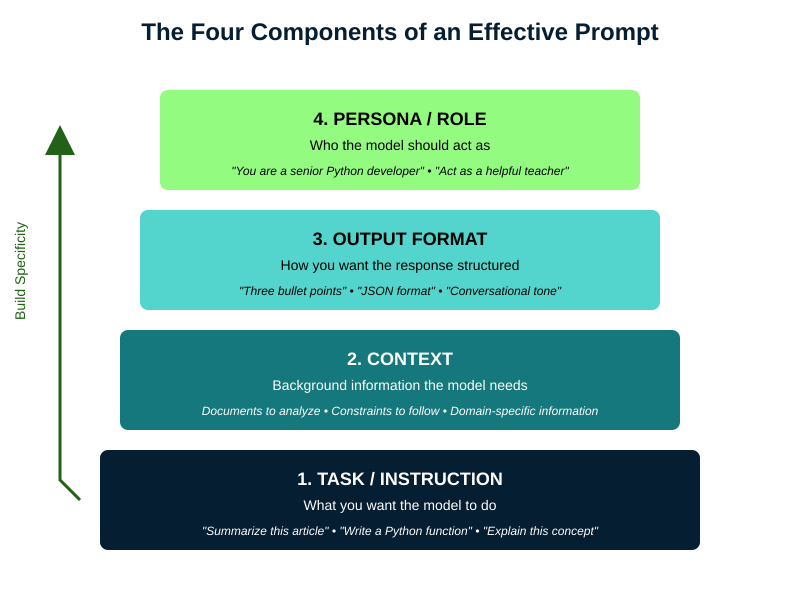

While different frameworks use slightly different terminology, research has converged around several core components that make prompts effective:

The Task or Instruction: What you want the model to do. "Summarize this article" or "Write a Python function" or "Explain this concept."

The Context: Background information the model needs. This might be a document to analyze, constraints to follow, or domain-specific information that shapes the response.

The Output Format: How you want the response structured. "Provide three bullet points" or "Write in JSON format" or "Use a conversational tone."

The Persona or Role: Who the model should act as. "You are a senior Python developer" or "Act as a helpful teacher for elementary school students."

These aren't rigid requirements. Simple prompts often need just a task. But understanding these components helps you diagnose why a prompt isn't working and how to fix it (Figure 1).

Context as External Knowledge

While the model knows a lot from training, you'll often need it to work with information it's never seen. Your company's internal documentation, a research paper published yesterday, or that peculiar API you're debugging. This is where context becomes crucial, not just as background information, but as the primary source of truth for the model's response.

The most straightforward approach is to paste your document directly into the prompt. But placement matters. For typical contexts, put your instructions first, then the context, then reiterate what you want done with it:

Analyze the following transcript for customer pain points and

summarize the top three issues mentioned.

TRANSCRIPT: [Your transcript here]

Based on the above transcript, list the top three customer pain

points with specific quotes as evidence.That repetition at the end isn't redundant. When there's a long document between your instruction and where the model starts generating its response, the instruction has less influence on what comes next. Restating your instruction after the context makes it more likely to follow through correctly. For very long documents (about 10 pages or more, like one of those recipe blogs where you have to scroll through the author's entire childhood memories before finding the ingredients), skip the detailed instructions at the beginning entirely. Just introduce the document, paste it, then put all your detailed instructions after it where they'll have maximum influence.

For longer documents, use clear delimiters and consider breaking them into labeled sections the model can reference:

Review this code for security vulnerabilities.

=== FILE: auth.py === [authentication code]

=== FILE: database.py === [database code]

Focus only on the code provided above. For each vulnerability

found, specify the file and line number.

Here's the critical part. When you provide external context, it can be helpful to explicitly tell the model to limit itself to that information. Otherwise, it might "helpfully" mix in its training knowledge, which could be outdated or irrelevant. The instruction, "Answer based only on the provided information" is a guard rail against hallucination. If the answer isn't in your provided context, you want the model to say so, not make something up. Add constraints like "If the document doesn't contain the answer, respond with 'This information is not in the provided document.'"

The model will still occasionally hallucinate details even when the correct information is right there in the context. It might paraphrase incorrectly, merge unrelated sections, or confidently cite line numbers that don't exist. This isn't malicious. Remember, the model is pattern-matching, not reading for comprehension. When accuracy matters, structure your prompt to make verification easier. Ask for direct quotes, specific section references, or step-by-step extraction of facts before synthesis.

Think of context like hiring a brilliant but overeager assistant who's never worked at your company and has been trained to appear careful and cautious. They need all the relevant documents, clear instructions about what to use and what to ignore, and explicit boundaries about when to admit they don't know something. Give them that structure, and they become incredibly useful. Leave them to guess, and you'll get creative fiction mixed with fact.

With the components understood, let's see why each prompting technique actually works and when it fails (Figure 2).

Starting Simple: Zero-Shot Prompting

The simplest approach is zero-shot prompting: you give an instruction without any examples. The term comes from machine learning, where "shot" refers to training examples (borrowed from "one-shot learning" in cognitive science, where humans learn from a single example). Zero shots means zero examples. You're asking the model to perform a task based solely on the instruction itself, with no demonstrations to guide it. This works well for common tasks the model has seen millions of times:

Translate this sentence to French: "I am traveling to Japan soon,

which side of the road do they drive on?"The model responds with, "Je voyage bientôt au Japon, de quel côté de la route conduisent-ils?" It doesn't just swap words mechanically. A word-for-word translation would be something like "Je suis voyageant à Japon bientôt..." which isn't even valid French. The construction is grammatically wrong, like saying "I am to traveling" in English. Instead, the model produces proper French grammar: "Je voyage" (I travel/I am traveling) and "conduisent-ils" (do they drive), because during training it learned these patterns from millions of French texts.

Now when my French friend replies with helpful advice from her recent trip, "Ils conduisent à gauche!", I might need the model to translate back, "They drive on the left!" One simple instruction, no examples needed, and the model handles it perfectly.

Zero-shot works because during the fine-tuning phase (after the initial training we discussed in an earlier white paper, What Makes Each LLM Different?), the model specifically learned to recognize instruction patterns. It saw millions of examples where variations on "Translate X to Y" were followed by proper translations, "Summarize this" was followed by summaries, and so on. The model is still just predicting the next token, but it's learned that certain patterns of tokens (instructions) should be followed by certain types of responses (following those instructions).

But zero-shot has limits. For complex, ambiguous, or highly specific tasks, the model has to guess what you want. And as we know from how these systems work, when they guess, they're just following statistical patterns, which might not align with your actual intent.

Teaching by Example: Few-Shot Prompting

If zero-shot prompting isn't getting the results you want, you can show what you want through examples. This is few-shot prompting, and it's remarkably powerful because it leverages the model's in-context learning ability.

In-context learning is the model's ability to adapt based on what you show it right now, in this conversation. Your examples become part of the context that the model's attention mechanisms (those components that help it figure out how words relate to each other) reference when generating a response. The model isn't "learning" in the way humans do. It's pattern-matching. When you provide examples, you're saying "find patterns in my examples and apply them to this new case.

Classify the sentiment of product reviews:

Review: "The product arrived damaged and customer service

was unhelpful."

Sentiment: Negative

Review: "Exceeded my expectations! Great value for money."

Sentiment: Positive

Review: "It works as advertised, nothing special but does the job."

Sentiment: Neutral

Review: "The interface is confusing but the features are

powerful once you learn them."

Sentiment:

The model sees the pattern (one-word labels that capture the overall feeling of the review) and continues it. This works because during training, the model learned that text following any repetitive structure (example, label, example, label, new example) typically continues with a similar label. You could create a completely novel structure the model has never seen before, like mapping reviews to colors or city names, and as long as you provide enough examples with a consistent logic, it would continue the pattern. The attention heads look back at your examples, see how you mapped reviews to sentiments, and apply that same mapping to the new review.

It may not be obvious when zero-shot is no longer sufficient and few-shot is necessary, but that's okay. Start with zero-shot and see if there are signs it needs examples: the model may misunderstand your categories (it may use "good", "bad" and "okay" when you need it to specifically use "negative", "positive" and "neutral"), or it may format its response wrong (you may require one-word answers, but it gives you full sentences). You can clarify what you want by providing examples, highlighting subtle distinctions or defining important rules. If you want the LLM to classify customer support tickets as "billing", "technical", or "feature request", the model might do well with most while struggling on edge cases, but with examples it can better match what you would do. Few-shot is especially useful when you have specific or uncommon rules that wouldn't be clear from simple instructions alone.

When Simple Prompting Isn't Enough

For tasks requiring multi-step reasoning, basic prompting often fails. The model tries to jump directly to an answer, skipping the intermediate thinking that would lead to a correct solution. This is where advanced techniques become essential. We'll explore three powerful approaches: Chain-of-Thought for sequential reasoning, Tree-of-Thoughts for exploring multiple solutions, and ReAct for grounding responses in external information.

Chain-of-Thought: Making the Model Show Its Work

Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting explicitly asks the model to break down its reasoning step by step. By forcing the model to articulate intermediate steps, you're giving the attention mechanisms (which connect related pieces of information across the text) more material to work with. Each step becomes context that later steps can reference.

This relates to but differs from dedicated "thinking" models like OpenAI's o1. Those models have been specifically trained to perform multi-step reasoning internally before responding. Standard models can still "think" through problems when you explicitly prompt them to, they just need you to ask. It's the difference between a student who automatically shows their work versus one who can show their work when the teacher requires it.

The simplest version requires just adding "Let's think step by step" to your prompt:

Question: If a store offers a 20% discount on an item that costs

$80, and then adds 8% sales tax to the discounted price, what is

the final price? Let's think step by step.This single phrase triggers a behavior the model learned during training: that step-by-step solutions follow this instruction. The model will calculate the discount, subtract it from the original price, calculate tax on the discounted amount, and add it to get the final answer.

For more complex problems, you can demonstrate the reasoning pattern with one or more examples before providing your unsolved problem:

Problem: I need to make dinner but I have dietary restrictions.

I'm vegetarian, allergic to nuts, and my guest is gluten-free.

What can I serve that works for everyone?

Solution: Let me work through this step-by-step.

- My restrictions: vegetarian (no meat/fish), no nuts

- Guest restrictions: no gluten (no wheat, barley, rye)

- Safe for both: vegetables, fruits, rice, quinoa, legumes,

dairy, eggs

- Good main dish options: rice bowls, quinoa salad, vegetable

curry with rice

- Decision: Vegetable curry with rice satisfies all requirements

Problem: I'm planning a trip from New York to Los Angeles. I have a

fear of flying, get carsick on long drives, and need to arrive by

Friday for a wedding. Today is Monday. What are my options?

Solution:

The model learns the pattern: identify the knowns, calculate derived values, combine for the final answer. This is actually a specialized form of few-shot prompting, but instead of just showing input-output pairs, you're showing the reasoning process itself. Regular few-shot teaches the model what kind of answer to give; Chain-of-Thought few-shot teaches it how to arrive at that answer.

Tree-of-Thoughts: Exploring Multiple Paths

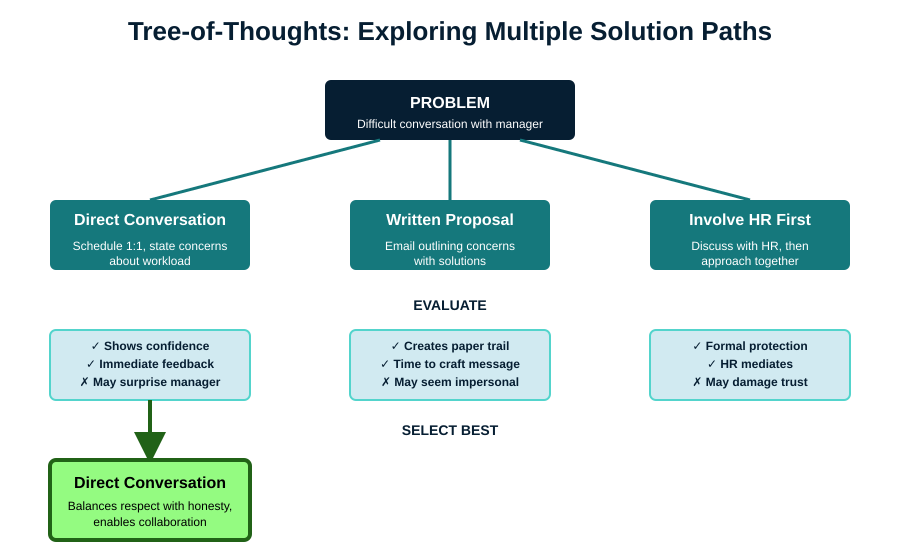

Some problems require exploring different approaches before finding one that works. Tree-of-Thoughts prompting makes the model consider multiple possibilities:

I need to write a persuasive email to my manager about working

remotely two days a week.

Generate three different approaches I could take, evaluate the pros

and cons of each, then recommend which would be most effective.With this prompt, the model will generate multiple strategies (maybe emphasizing productivity, work-life balance, or proposing a trial period), weigh their strengths and weaknesses, then select the best path. This isn't just brainstorming, it's structured exploration where each path gets evaluated before proceeding. You can further expand this strategy by providing background information on both people involved and add, "Consider from both perspectives."

You can also seed the model with initial ideas if you have some directions in mind but want help developing and evaluating them:

I need to write a persuasive email to my manager about working

remotely two days a week.

Consider these approaches (and any others you think of):

- Emphasizing increased productivity from fewer interruptions

- Proposing a trial period with success metrics

For each approach, evaluate the pros and cons, then recommend

which would be most effective.

This hybrid approach combines your domain knowledge with the model's ability to expand on ideas and spot potential issues you might have missed. The model might add a third approach you hadn't considered, or identify risks in your proposed strategies that weren't obvious.

But there's a tradeoff: providing initial ideas can anchor the model to your thinking and prevent more creative solutions. If you suggest two conventional approaches, the model might just add another conventional one rather than proposing something unexpected. Sometimes the best insights come from letting the model approach the problem fresh, without your assumptions about what's reasonable or appropriate. The choice depends on whether you need thorough exploration of known strategies or genuinely novel ideas.

Of course, you're not limited to one attempt. Try it without suggestions first to see what creative solutions emerge, then start with a new chat and try again with your specific ideas if you want deeper exploration of particular approaches. Unlike asking a human colleague, you can have the same conversation multiple ways without wearing out your welcome.

The key difference between Tree-of-Thoughts and just asking for "three options" is depth and commitment. When you simply ask for options, the model often generates surface-level alternatives that sound different but aren't genuinely distinct approaches. By explicitly requiring development, evaluation, and selection, you force deeper exploration. It's the difference between "Option A: Be direct, Option B: Write a letter, Option C: Talk to HR" and actually thinking through what each approach would entail, what could go wrong, and why one might work better than others given your specific context.

Like with Chain-of-Thought, you can also use few-shot prompting to demonstrate the Tree-of-Thoughts pattern:

Problem: How should I ask my neighbor to stop playing loud

music at night?

Approach 1: Direct conversation

- Pro: Clear communication, builds relationship

- Con: Might create confrontation

Approach 2: Written note

- Pro: Non-confrontational, gives them time to process

- Con: Could seem passive-aggressive

Approach 3: Contact building management

- Pro: Keeps me anonymous

- Con: Escalates without trying to resolve directly

Best approach: Start with Approach 1 because...

Problem: How should I handle a coworker taking credit for my

ideas in meetings?

Where Chain-of-Thought follows one path to its conclusion, Tree-of-Thoughts maps out multiple routes before choosing the best one (Figure 3).

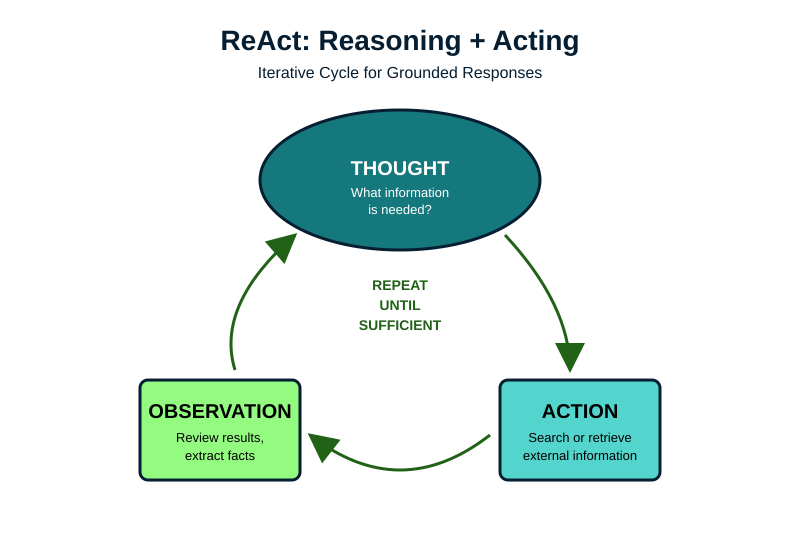

ReAct: Connecting to the Real World

The ReAct (Reason + Act) framework addresses one of LLMs' fundamental limitations: they can't verify facts or access current information. While many modern LLMs handle this automatically when they detect you need current data, you can explicitly trigger more thorough research by structuring your prompts to request step-by-step verification.

The pattern is simple: the model thinks about what it needs, takes an action to get that information, observes the result, then repeats until it has enough to answer your question (Figure 4):

Question: Is the restaurant Chez Panisse still open, and can I

make a reservation for this weekend?

Thought: I need to check the current status of Chez Panisse

restaurant. Let me search for this.

Action: Search["Chez Panisse restaurant Berkeley current

status 2025"]

Observation: Chez Panisse is open Tuesday through Saturday for

dinner service.

Thought: Now I need to find out how to make reservations.

Action: Search["Chez Panisse reservation system"]

Observation: Reservations open on Resy.com at midnight exactly

28 days before the dining date.

Thought: I should check what day this weekend falls on to give

specific guidance.

Action: Get_current_date[]

Observation: Today is Thursday, October 2, 2025.

Thought: This weekend would be October 4-5 (Saturday-Sunday).

Since they're closed Sunday and reservations open 28 days prior,

those dates would have opened in early September and are likely

fully booked. Let me verify.

Answer: Chez Panisse is still open, serving dinner Tuesday through

Saturday. For this weekend, you would need to check Resy.com,

though reservations opened 28 days ago so availability is unlikely.

For future visits, set a reminder to book at midnight exactly

28 days before your desired date.

This Thought-Action-Observation cycle continues until the model has enough information to answer. It's especially powerful because it addresses the hallucination problem directly by grounding responses in verifiable external data. Instead of guessing or generating plausible-sounding information about restaurant hours, the model retrieves actual facts.

Most modern LLM interfaces implement ReAct automatically, but you can prompt for more thorough grounding. Instead of "What's the current Bitcoin price?", try "First check the current Bitcoin price, then compare it to last week's price, then explain what factors might account for any change." This explicit step-by-step structure triggers more comprehensive searches and cross-referencing. When accuracy is critical, you can also add constraints like "Verify this information from multiple sources" or "Check if this information has changed in the last 24 hours" to ensure the model doesn't rely on potentially outdated training data.

The Art of Being Specific

The single most important principle in prompt engineering is specificity. Vague prompts produce inconsistent outputs because the model has to guess what you want. Consider these two prompts:

Vague:"Write something fairly short about climate change. Explain it simply and format it nicely."

Specific:"Write a 100-150 word explanation of how rising ocean temperatures affect coral reefs, using only words a 10-year-old would understand. Use bullet points with bold headers."

The second prompt eliminates ambiguity about length, audience, scope, and style. The model doesn't have to guess. You've constrained the probability space to exactly what you want.

This extends to every aspect of your prompt:

- Instead of "fairly short," specify "100-150 words"

- Instead of "explain simply," specify "explain using only words a 10-year-old would understand"

- Instead of "format nicely," specify "use bullet points with bold headers"

Structuring Complex Prompts

When prompts become complex with multiple components, structure prevents confusion. While the model's attention mechanism processes all words and their relationships, unstructured prompts make it harder for the model to identify and prioritize different requirements. A wall of text with jumbled instructions increases the chance that some requirements get overlooked or misinterpreted.

Clear structure helps by using delimiters (like Markdown headers with ###, XML tags, or triple quotes) to separate distinct sections. Place critical instructions at the beginning where they're most likely to be noticed, and consider repeating essential constraints at the end as reinforcement. Here's how structure transforms an overwhelming prompt into something manageable:

### ROLE ###

You are a technical documentation specialist with 10 years

of experience.

### TASK ###

Review the following API documentation and identify issues with

clarity, completeness, and accuracy.

### CONTEXT ###

This documentation is for junior developers who are new to

REST APIs.

### INPUT ###

[Your API documentation here]

### OUTPUT FORMAT ###

Provide your review as:

1. Executive Summary (2-3 sentences)

2. Critical Issues (must fix)

3. Suggestions (nice to have)

4. Positive Aspects (what works well)

### CONSTRAINTS ###

- Focus only on documentation quality, not API design

- Provide specific examples for each issue identified

- Keep total response under 500 words

The delimiters aren't magical. They're just markers that help the model's attention mechanism recognize distinct sections. This same principle applies whether you're asking for code review, content creation, or data analysis. Structure your complex prompts and the model is far more likely to address all your requirements.

Iterative Refinement: Your Prompts Are Hypotheses

Effective prompt engineering is empirical. Your first prompt is a hypothesis about what will produce the desired output. The model's response is your experimental result. Based on what you observe, you refine and try again.

Start simple. If you need a product description, begin with:

Write a product description for a wireless keyboard.Evaluate the output. Too long? Add length constraints. Wrong tone? Specify the audience or provide an example of the right tone (like sharing a previous product description you wrote that nails the voice you want). Missing key features? Provide them as context. Each iteration teaches you what the model assumes versus what needs to be explicit.

But there's an important caveat. Too much back-and-forth in the same conversation can pollute the context and create confusion. The model sees your entire conversation history, including all your failed attempts and corrections. After a few iterations, this cluttered context can actually make outputs worse, not better.

When you finally get output that works, save the prompt that produced it. Even better, ask the model what made it work. "What specific instructions in my prompt produced this style of output?" The model can spot patterns you might miss. Maybe a particular phrase triggered the right tone, or a constraint shaped the response in an unexpected but useful way. Build a collection of these working prompts. Next time you need similar output, you can start from a known-good template instead of iterating from scratch.

Once you've figured out what works, start fresh. Either edit your original prompt directly (replacing the version that didn't work) or begin a new conversation with your refined prompt. Think of it like editing a document. At some point, you need a clean draft rather than a page full of crossed-out sentences and margin notes.

Common Failure Modes and Fixes

Understanding why prompts fail helps you fix them faster. Let's look at the most common problems and their solutions.

The model agrees with everything you say. This sycophancy problem is real and it actively makes your outputs worse. When you share an idea, the model tends to praise it as brilliant even when it's mediocre. If you ask "Is this good?" the model will find reasons to say yes. The fix isn't demanding criticism (which just creates false negatives) but asking for specific analysis. Instead of "What do you think of my business plan?" try "Compare this approach to how Stripe handled the same problem" or "Analyze the revenue projections against standard SaaS benchmarks." When you need genuine evaluation, frame prompts around concrete criteria rather than general quality judgments. The model can pattern-match against specific standards much better than it can determine abstract "goodness."

The model ignores your constraints. This often happens with negative instructions ("don't do X"). Models handle positive instructions ("do Y instead") more reliably. If you tell the model "don't use technical terms," it might still use them, but if you say "use everyday language that a teenager would understand," it's more likely to comply. When critical instructions keep getting missed, try placing them at the beginning of your prompt where they're most prominent, repeating essential constraints at the end as reinforcement, or breaking complex prompts into sequential steps.

The output is generic or vague. This happens when the model falls back on the most common patterns from its training because you haven't given it enough direction. A prompt like "write about productivity" will produce the same tired advice about time-blocking and eliminating distractions that appears in thousands of blog posts. Add specific context, unique angles, or concrete requirements to push the model beyond these defaults.

Hallucinated information. For factual tasks, explicitly instruct the model to acknowledge uncertainty. Tell it: "Answer based only on the provided information. If the information doesn't contain the answer, say 'I cannot determine this from the provided information.'" This helps prevent the model from inventing plausible-sounding guesses to fill gaps.

Inconsistent formatting. Abstract descriptions like "make it professional" mean different things to different people. A more effective approach is to provide examples of the exact format you want. The model pattern-matches much better with concrete examples than vague descriptors.

Working with Your LLM's Limitations

Since LLMs work through pattern-matching, they excel at combining patterns in novel ways but can't verify truth or discover genuinely new information. Design your prompts accordingly.

For creative tasks, embrace the model's ability to combine patterns in unexpected ways. Want a story that blends noir detective fiction with space opera? The model has seen both genres and can weave them together in ways that might surprise you. For factual tasks, provide source material or use retrieval-augmented approaches where the model searches for information before responding. For reasoning tasks, make the steps explicit through Chain-of-Thought prompting to prevent the model from jumping to conclusions. For critical applications, always validate the output, especially anything involving numbers, dates, or specific claims.

The model will confidently produce plausible-sounding text whether it's correct or not. It doesn't know what it doesn't know. Your prompts should channel this confidence toward patterns you know are valid. If you're using it to draft legal documents, provide templates and examples from verified sources. If you're generating code, test everything.

Beyond Individual Prompts

As your use cases become more sophisticated, you'll find single prompts insufficient. Complex tasks often require prompt chaining, where you break the task into steps, with each prompt building on the previous output.

Imagine you need to analyze a lengthy research paper and create an executive summary. Instead of asking for everything at once, you might chain prompts like this: First, extract key facts and findings from the document. Second, organize those facts into thematic categories. Third, generate a one-page summary from the categorized facts. Each step has a focused objective the model can handle well, rather than trying to juggle multiple complex requirements simultaneously.

This approach is more reliable because it mimics how humans tackle complex problems: one piece at a time. When you ask for everything at once, you're essentially asking the model to keep track of extraction rules, categorization logic, and summarization guidelines all at the same time. Something usually gets dropped. By breaking it apart, each prompt can be optimized for its specific task, and you can verify the output at each stage before moving forward.

The Path Forward

Prompt engineering is evolving rapidly. What works today might be obsolete as models improve. But the fundamental principles of clarity, specificity, appropriate structure, and empirical refinement will remain relevant because they address how these models fundamentally work. These same principles, incidentally, make you a better communicator with people too. Being clear about what you want, providing appropriate context, and structuring complex requests into manageable pieces works just as well with your colleagues as it does with an LLM.

The key is to remember what you learned about LLMs’ internals. They’re finding patterns, not thinking. They’re calculating probabilities, not understanding meaning. When your prompts work with these mechanisms rather than against them, you get better results.

Start with simple, clear instructions. Add examples when patterns aren’t obvious. Structure complex prompts to prevent important details from getting lost. Break reasoning tasks into explicit steps. Ground factual queries in source material. Test and refine based on what actually comes back, and when something works, understand why so you can replicate it.

These models are tools, powerful but limited. They can’t verify the truth, they can’t truly reason, and they’ll confidently generate nonsense if that’s what the patterns suggest. But they can also help you explore ideas faster than ever before, generate creative combinations you might never have considered, and handle routine writing tasks that used to eat up hours of your day.

If you’ve been frustrated by LLMs giving you nonsense or missing the point entirely, now you understand why these problems happen and how to avoid them. Armed with these techniques, you should be able to get much more useful outputs. The difference between a vague mess and a useful response often comes down to how you structure your request.