How-to Guide

Part 1: Tokenization, Building an LLM From Scratch in Rust

December 8, 2025

This How-To Guide, walks readers through how we build a language model from scratch in Rust, starting with the tokenizer. In Part 1 we explain how text is turned into numbers using Byte Pair Encoding, why this step shapes everything the model can and cannot do, and how different vocabulary sizes affect compression, speed, and training behavior.

By Part 5, readers will have a working transformer trained on Shakespeare and a clear understanding of how every part of the model works.

Introduction

We're building Feste, a complete GPT-2 style transformer from first principles in Rust, trained on Shakespeare's complete works. This multi-part series documents that journey, implementing every core component—from tensor operations to multi-head attention—to demystify how a modern language model works. Our first step is the critical transformation of human language into data the model can use: tokenization.

Language models don't read text. They read numbers. This fundamental fact explains most of the weird things you've noticed about ChatGPT, Claude, or any other LLM. They can't count letters in a word reliably. They're sensitive to spacing. They struggle with reversing text or doing character-level operations. They handle some words better than others, seemingly at random.

Building a language model from scratch is the best way to understand why. We can discover whether these quirks are fundamental limitations or modifiable design choices. We can explore how each component works and how changes ripple through the system. The first step in this journey is the transformation from text to numbers that happens in the tokenizer.

What We're Building

Throughout this series, we will build Feste, a GPT-2 style transformer trained on Shakespeare's complete works. GPT-2 is the architecture OpenAI released in 2019 that proved you could train a language model to generate coherent text by predicting one word at a time based on all the words that came before it. Most language models in use today are built on this same foundation.

Most people build transformers using PyTorch or TensorFlow, libraries that abstract away the math so you can focus on architecture. We're implementing every component from first principles in Rust instead. We could use Python, which is what most people reach for when building machine learning projects, but Python abstracts away too much. Rust gives us low-level control over memory and performance, and the borrow checker forces us to think clearly about ownership and memory safety. We've been using Rust at Tag1 for years, particularly for performance-critical work like our load testing framework Goose. For a learning exercise where understanding every component is the point, that same discipline is exactly what we need.

We named Feste after the fool in Shakespeare's Twelfth Night, and we're training it on Shakespeare's complete works. Shakespeare is public domain, which means anyone can reproduce this from scratch with nothing but the code and the data.

By the end of this series, you'll have a working GPT-2 style transformer that trains on real data and generates coherent text. By the end of this first part, you'll understand why tokenization shapes everything the model can and cannot do.

Why Tokenization Matters

Before we can train a neural network on text, we need to convert that text into numbers. The tokenizer isn't a preprocessing step you can ignore. It's an integral part of the model architecture, and you can't evaluate model capabilities without understanding it.

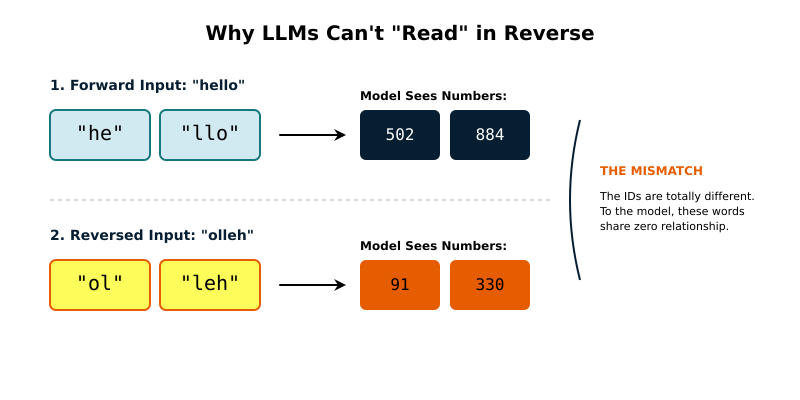

Every quirk you've noticed in language models traces back to tokenization. The tokenizer determines what the model actually sees. When it can't count letters, that's because it sees tokens like ["run", "ning"], not individual characters. When spacing matters, that's because " hello" and "hello" tokenize differently. Rare words break into unfamiliar token pieces the model rarely encountered during training. Reversing the letters in text is hard because "hello" might be tokenized as ["he", "llo"], but "olleh" breaks down completely differently. (Figure 1):

Feste implements Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), the same algorithm GPT-2 uses. The goal is straightforward: convert raw text into token IDs a neural network can process, and convert those IDs back into text.

Why BPE?

The naive approach to tokenization is to map each unique word to a number. But this fails immediately. How many unique words exist in English? Hundreds of thousands, easily. And that's just English. What about other languages? What about code? What about made-up words or typos?

Character-level tokenization solves the vocabulary problem by treating each character as a token. But now sequences are extremely long, and the model has to learn how to compose characters into words from scratch. It's like asking the model to learn spelling and language simultaneously.

BPE finds a middle ground by working at the byte level. Every file on your computer is stored as bytes. A byte is eight binary digits, which means it can represent exactly 256 different values (0 through 255). Text files are sequences of bytes that represent characters according to encoding rules like UTF-8.

In UTF-8, common English characters use one byte each. The letter "A" is stored as byte 65. The letter "z" is byte 122. But characters from other writing systems use multiple bytes. Japanese "日" is stored as three bytes in sequence. Arabic "ع" is two bytes. Emoji use four bytes.

BPE starts with these 256 possible byte values as the base vocabulary. Every byte that exists in the file gets its own token. Then it iteratively merges the most frequent adjacent pairs into new tokens. If the bytes for "th" appear together constantly in English text, they get merged into a single token. If the three-byte sequence for a common Japanese character appears frequently, those bytes get merged into one token.

Common words end up with their own tokens. Rare words break down into familiar byte sequences that the tokenizer has seen in other contexts. The vocabulary size is configurable and fixed. Most importantly, this works for any language, any alphabet, any writing system, because everything is just bytes underneath.

There is a deeper reason we use BPE: it raises the abstraction level of the model. If a model sees the sequence ['c', 'a', 't'], it must spend its limited neural capacity learning that these three characters often go together. If it sees the single token ['cat'], it can immediately focus on learning how that concept relates to ['dog'] or ['meow']. A smaller vocabulary forces the model to act as a spell-checker, assembling words from fragments. A larger vocabulary allows the model to think in concepts, provided we have enough data to teach it what those concepts mean.

For this series, we're focusing on text tokenization. Language models also handle images, audio, and video, but those use separate encoding systems. We'll stick to what Feste does: convert text to numbers and back again.

The Algorithm

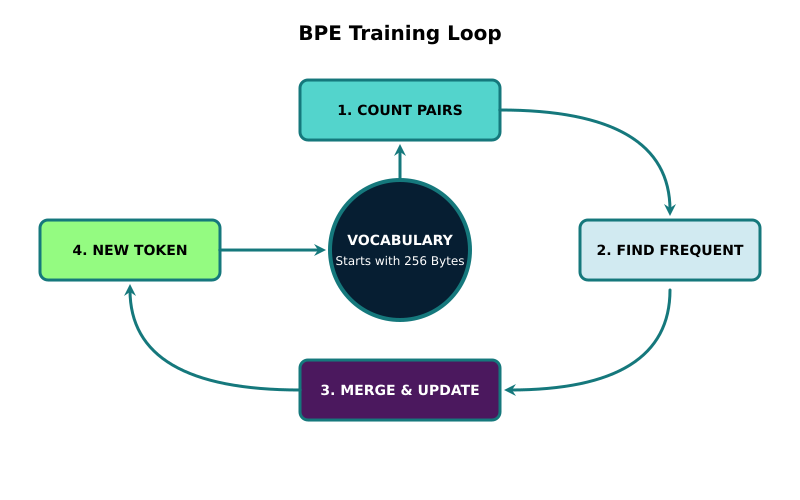

BPE training works like this (Figure 2):

Start with bytes. Create 256 base tokens, one for each possible byte value (0-255). In Feste, we encode them as hex strings like <00>, <01>, up to <ff>. Byte 65 is <41>, which is the letter "A" in UTF-8. Byte 32 is <20>, which is a space.

Count adjacent pairs. Scan through the corpus and count how often each pair of tokens appears next to each other. Maybe <65> (lowercase 'e') followed by <20> (space) appears 130,000 times because "e " is so common in English.

Merge the most frequent pair. Create a new token representing that pair. This becomes token 256 in the vocabulary. Replace all instances of that pair with the new token throughout the corpus.

Repeat. Continue finding the most frequent pair, merging it, and updating the corpus until the vocabulary reaches your target size.

The merges learned during training become the tokenizer's rules. When encoding new text, you apply these rules in order to convert it into tokens.

This is why tokens can be anything. A token might be a single byte for space or punctuation. It might be a common pair like "th". It might be an entire word like "the" or even " the " (space-the-space) if that sequence appears frequently enough. The algorithm doesn't care about linguistic boundaries. It only cares about frequency.

Implementation Details

Our tokenizer maintains three key pieces of state:

pub struct BPETokenizer {

vocab: HashMap<String, usize>, // Maps token strings to IDs

merges: Vec<(String, String)>, // Merge rules in order

unk_token: String, // Unknown token (unused for now)

}The vocabulary starts with 256 entries mapping hex-encoded bytes to IDs 0-255. During training, we add new entries for each merge. The merge rules are stored in a vector because order matters during encoding.

When you encode text, you must apply the merges in the exact order they were learned. Say merge 1 learns that <74><68> (the bytes for "th") should become token 256. Then merge 50 learns that token 256 + <65> ("the") should become token 300. When you encode "the", you apply merge 1 first to create token 256, then apply merge 50. Apply them out of order and you won't find the patterns.

Decoding is simpler. You just look up each token ID in the vocabulary and convert it back to its byte sequence. No merge order needed.

The training process is completely deterministic. Given the same corpus and vocabulary size, BPE will always learn the exact same merges in the exact same order. Count all pairs, find the most frequent, merge it. Count again, find the most frequent, merge it. No randomness. This is why you can train a tokenizer once, save it, and use it forever. When you see random output from the model later, that's the model making bad predictions about which tokens to generate. The tokenizer itself just converts between text and tokens deterministically.

Training Performance

The core training loop has a severe performance bottleneck: counting adjacent pairs in the corpus. With millions of bytes and potentially thousands of merges to learn, a straightforward single-threaded implementation would take hours.

Feste uses Rayon, a Rust library, to parallelize pair counting across CPU cores. The details of parallelization aren't important for understanding tokenization, but the speedup makes experimentation practical.

let pair_counts: HashMap<(String, String), usize> = tokens

.par_chunks(chunk_size)

.enumerate()

.fold(HashMap::new, |mut local_counts, (chunk_idx, chunk)| {

// Count pairs within this chunk

for window in chunk.windows(2) {

let pair = (window[0].clone(), window[1].clone());

*local_counts.entry(pair).or_insert(0) += 1;

}

// Handle chunk boundaries...

local_counts

})

.reduce(HashMap::new, |mut a, b| {

// Merge counts from all chunks

for (pair, count) in b {

*a.entry(pair).or_insert(0) += count;

}

a

});This splits the corpus into chunks and counts pairs in parallel. But what about pairs that span chunk boundaries? If chunk 1 ends with "th" and chunk 2 starts with "e", we'd miss counting "the". We handle this explicitly by having each thread check its chunk boundary and count the pair between its last token and the next chunk's first token. No pairs are missed.

On a modern multi-core system, this gives roughly 2-3x speedup. We optimize the worst bottleneck, pair counting, to keep experimentation practical, but we do not aim for maximum performance. Other operations like applying merges and updating the corpus stay sequential because optimizing them would complicate the code without significantly improving iteration speed for our purposes.

For very large vocabularies, Feste trains on a 200KB sample instead of the full 5.5MB corpus. The most frequent pairs appear with similar relative frequencies in any sample. Training on the sample is orders of magnitude faster and achieves only 0.34% different compression on test data. Once training completes, the learned merges work perfectly on the full corpus or any other text.

Encoding Performance

Encoding applies the learned merge rules to convert text into token IDs. We process each rule in order, walking through the current token sequence once, checking if we see the pair that should be merged. When we find it, we output the merged token and skip ahead. When we don't, we output the current token and move forward one position.

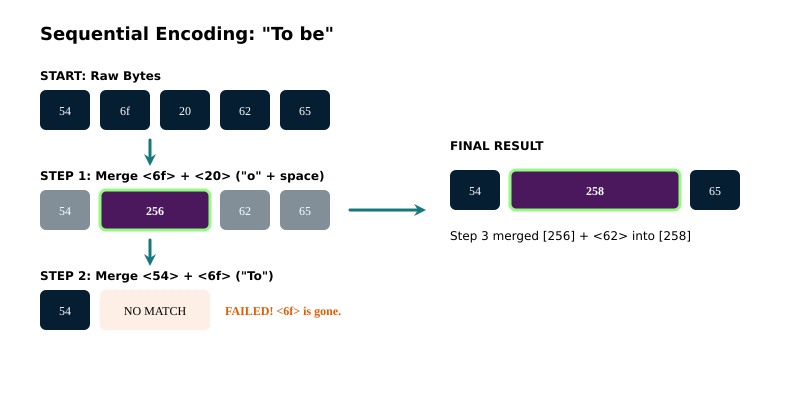

Let's see how this works with "To be":

"To be" -> [<54>, <6f>, <20>, <62>, <65>] (bytes in hex)

Say we've learned three merges in order:

<6f><20> (o-space) becomes token 256

<54><6f> (To) becomes token 257

Token 256 + <62> becomes token 258

Applying these merges sequentially transforms the token list from [<54>, <6f>, <20>, <62>, <65>] into [<54>, 258, <65>].

Merge 1 finds <6f><20> and replaces it with token 256. The list becomes [<54>, 256, <62>, <65>].

Merge 2 looks for <54><6f>. But the list now has <54> followed by 256, not <6f>, so there's no match and the list stays the same.

Merge 3 finds token 256 followed by <62> and replaces it with token 258. The final list becomes: [<54>, 258, <65>].

The order matters because earlier merges change what later ones can match. Merge 1 consumed the <6f> byte, so merge 2 can't find its pattern anymore (Figure 3).

As a simple optimization we build a new vector rather than modifying the existing one in place. If we deleted from the middle of the vector everything after would have to be shifted. Instead we walk through the old vector once, copy what's needed, and touch each token only once.

let mut new_tokens = Vec::with_capacity(tokens.len());

let mut i = 0;

while i < tokens.len() {

if i < tokens.len() - 1 && tokens[i] == *pair_a && tokens[i + 1] == *pair_b {

new_tokens.push(merged.clone());

i += 2; // Skip both tokens in the pair

} else {

new_tokens.push(tokens[i].clone());

i += 1;

}

}

tokens = new_tokens;We also use a parallelization strategy for encoding. We split the text into chunks, encode each chunk on a separate core, then combine the results.

Unlike our training step, strict BPE requires handling merges that might straddle the boundary between two chunks (e.g., splitting "formatting" into "format" and "ting"). In production, you would implement complex boundary stitching to catch these. For this educational model, we process chunks independently. The speedup is massive, and the loss in compression efficiency is negligible.

Decoding

Decoding converts token IDs back to text by looking up each ID in the vocabulary and parsing the hex-encoded bytes back to characters.

Taking our "To be" example, we encoded it to [<54>, 258, <65>]. Decoding reverses the process. Look up token <54> in the vocabulary, it maps to the hex byte <54>. Look up token 258, it maps to <6f><20><62> (the merged "o b" sequence). Look up <65>, it maps to <65>. Join them together: <54><6f><20><62><65>. Parse the hex bytes back to UTF-8: "To be".

pub fn decode(&self, ids: &[usize]) -> String {

// Create reverse vocabulary map (ID -> token string)

let id_to_token: HashMap<usize, String> = self

.vocab

.iter()

.map(|(token, id)| (*id, token.clone()))

.collect();

// Convert IDs back to token strings

let tokens: Vec<String> = ids

.iter()

.filter_map(|id| id_to_token.get(id).cloned())

.collect();

// Join all tokens and decode using the shared hex-parsing logic

let merged = tokens.join("");

self.decode_token(&merged)

}The process is straightforward: invert the vocabulary map so you can look up by ID instead of token string, convert each ID to its token, join them together, and parse the hex bytes back to UTF-8.

Training Results

The Feste repository includes an example called 01_train_tokenizers.rs, which trains five different tokenizers on Shakespeare's complete works using vocabulary sizes of 256, 512, 1024, 1536, and 20,534. The Shakespeare corpus from Project Gutenberg contains 5,422,721 bytes (about 5.5MB), large enough to see meaningful patterns while training in reasonable time.

We chose these vocabulary sizes to align with training examples we'll discuss in future posts. The largest, 20,534 tokens, approaches what production models use. GPT-2 and GPT-3 both use 50,257 tokens.

Understanding Compression

Compression ratio tells us how many bytes of input each token represents on average. A 1.96x ratio means one token represents 1.96 bytes. This matters for two reasons: shorter sequences and smaller vocabularies mean less data for the model to process during training and inference. A model processing 2.77 million tokens instead of 5.4 million tokens processes information faster and requires less memory. The model also needs fewer embedding parameters. Each token in the vocabulary requires its own row in the embedding matrix, so a 512-token vocabulary uses far fewer parameters than a 20,534-token vocabulary. The trade-off is encoding cost: better compression requires checking more merge rules.

Vocabulary Size 256 (Byte-level Only)

No merges are learned. The vocabulary contains exactly 256 tokens, one for each possible byte from `<00>` through `

Vocabulary size: 256

Encoded length: 5,422,721 tokens

Compression ratio: 1.00x

Training time: 0.00s

Encoding time: 0.14s

The encoded length matches the byte count exactly. One token per byte. The compression ratio is 1.00x because we're not compressing anything. This is the starting point before BPE does any work.

Vocabulary Size 512

Learning 256 merges is quick. The most frequent pair is `<65><20>` (the letter `'e'` followed by space), which appears 130,461 times in Shakespeare's works. This makes sense, as the text `"the "` is very common in English writing. The vocabulary contains one token per byte, and another 256 tokens representing merges.

Vocabulary size: 512

Encoded length: 2,772,080 tokens

Compression ratio: 1.96x

Training time: 25.54s

Encoding time: 2.04s

Common patterns like "e ", "th", "t ", "and ", "you" now get single tokens. Compression nearly doubles because frequent sequences no longer need multiple bytes. Also notice that encoding time starts to increase. With 256 merge rules to check, encoding requires more computation than simple byte mapping.

Example tokenizations:

"To be or not to be" -> 6 tokens: [To |be |or |not |to |be]

"Romeo and Juliet" -> 9 tokens: [R|om|e|o |and |J|u|li|et]

"Wherefore art thou" -> 8 tokens: [Wh|er|e|for|e |ar|t |thou]

Vocabulary Size 1024

With 768 merges, training takes longer as we scan for more pairs. Compression improves to 2.48x.

Vocabulary size: 1024

Encoded length: 2,189,778 tokens

Compression ratio: 2.48x

Training time: 77.45s

Encoding time: 4.88s

Common words like `"be"`, `"or"`, `"not"`, `"and"` get their own tokens. Less common words like `"Wherefore"` are split into pieces the tokenizer has seen before.

Training time roughly triples from vocab 512, and encoding time more than doubles. More merge rules mean more work both during training and during encoding.

Example tokenizations:

"To be or not to be" -> 6 tokens: [To |be |or |not |to |be]

"Romeo and Juliet" -> 8 tokens: [Rom|e|o |and |J|u|li|et]

"Wherefore art thou" -> 5 tokens: [Wh|ere|fore |art |thou]

Notice that "Wherefore" now splits into just 3 pieces instead of 5. The tokenizer learned "ere" and "fore" as common patterns.

Vocabulary Size 1536

Training 1,280 merges takes significantly longer. Compression reaches 2.78x.

Vocabulary size: 1536

Encoded length: 1,952,470 tokens

Compression ratio: 2.78x

Training time: 142.51s

Encoding time: 7.46s

The tokenizer now knows longer patterns and more domain-specific vocabulary. Words and phrases that appear frequently in Shakespeare get dedicated tokens.

However, raw compression isn't the only metric. Even though 1536 provides decent compression, it still fragments many distinct concepts. In our early experiments, we found that proper names and thematic words (like 'Love' or 'Shakespeare') were still being broken into multiple tokens at this level. This forces the model to memorize rigid character sequences just to output a name, making it more fragile during generation. A vocabulary that is too small can effectively 'mute' a smart model by forcing it to speak in syllables.

Example tokenizations:

"To be or not to be" -> 6 tokens: [To |be |or |not |to |be]

"Romeo and Juliet" -> 8 tokens: [Rom|e|o |and |J|u|li|et]

"Wherefore art thou" -> 4 tokens: [Wh|erefore |art |thou]

Now "Wherefore" is down to just 2 pieces: "Wh" and "erefore". The tokenizer has learned this archaic word pattern from Shakespeare's frequent use. However, the common phrases remain unchanged as there's a limit to how much you can compress already-efficient tokenizations.

Vocabulary Size 20,534

With 20,278 merges, we're training a production-scale tokenizer. This completes in minutes rather than hours thanks to the sampling optimization, only slightly longer than the 1536-token vocabulary despite being 13x larger. This is because the implementation uses sampling optimization for large vocabularies, training on a representative sample rather than the full corpus. Without sampling, training time would scale roughly linearly with vocabulary size and take hours.

Vocabulary size: 20,534

Encoded length: 1,481,106 tokens

Compression ratio: 3.66x

Training time: 286.34s

Encoding time: 242.50s

Compression improves dramatically to 3.66x. Many common phrases, character names, and domain-specific terms get dedicated tokens. But encoding time jumps to 242 seconds, nearly 8x longer than 1536. With 20,278 merge rules to check, the trade-off becomes clear: better compression at the cost of slower encoding and more parameters for the model.

Example tokenizations:

"To be or not to be" -> 5 tokens: [To |be |or |not to |be]

"Romeo and Juliet" -> 8 tokens: [R|ome|o |and |J|u|li|et]

"Wherefore art thou" -> 4 tokens: [Wh|erefore |art |thou]

At this scale, "not to" appears as a single token, which is phrase-level compression. Yet "Romeo and Juliet" still splits into 8 tokens because these proper names don't appear frequently enough in the training data to earn their own tokens.

Trade-offs

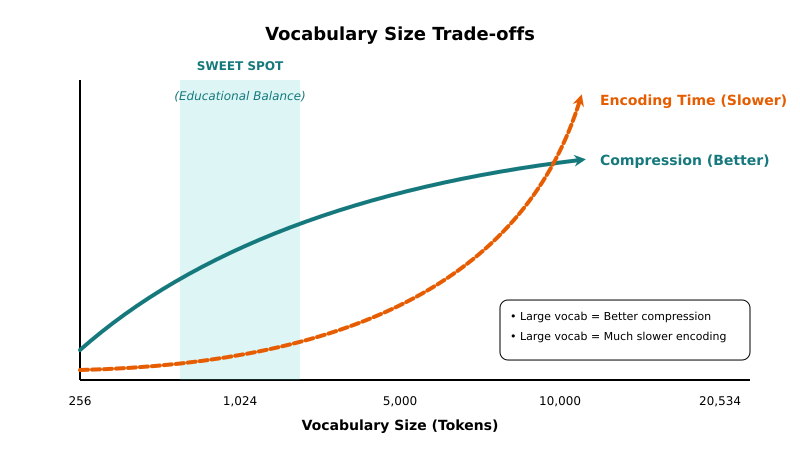

Let's visualize how vocabulary size affects our three key metrics:

Compression Ratio (higher is better):

256: 1.00x ████

512: 1.96x ████████

1024: 2.48x ██████████

1536: 2.78x ███████████

20534: 3.66x ███████████████

Training Time (illustrative based on our test machine):

256: 0s

512: 25s ████████

1024: 77s ████████████████████████████

1536: 143s ███████████████████████████████████████████████████

20534: 286s* ████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████

* Uses sampling optimization for large vocabularies

Encoding Time (illustrative based on our test machine):

256: 0.02s █

512: 2.04s ████████████████████

1024: 4.88s ████████████████████████████████████████████████

1536: 7.46s ██████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████

20534: 242.50s ████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████

There are some clear patterns:

Compression improves with vocabulary size, but with diminishing returns. The jump from 256 to 512 nearly doubles compression, but 1536 to 20534 only improves it by ~32%.

Training time increases roughly linearly with vocabulary size (until sampling optimization kicks in). Training 1536 takes about 143 seconds, and 20534 takes 286 seconds (though the exact time may vary based on hardware), but it was the sampling optimization that prevented continued exponential growth.

Encoding time grows dramatically with vocabulary size. While the model processes shorter sequences, creating those sequences becomes expensive. This is the fundamental trade-off of large vocabularies (Figure 4).

Choosing the Right Vocabulary Size

Choosing the right vocabulary size requires balancing computational cost against sequence length and the amount of training data available. Larger vocabularies increase the size of the embedding matrix because the model has to memorize more individual words. Smaller vocabularies result in longer sequences which makes training slower.

The most critical factor is often data scarcity. If you choose a massive vocabulary but only have a small dataset like Shakespeare, many tokens might appear only once. The model never sees enough examples to learn what they mean. This leads to embedding collapse where the model treats rare words as random noise.

We also found significant limits to going too small. With only 1536 tokens, distinct concepts like Love or Shakespeare still break down into multiple fragments. This forces the model to memorize rigid character sequences just to output a name. It effectively mutes a smart model by forcing it to speak in syllables. We suspect a larger vocabulary might fix this by capturing full words as single tokens, a theory we will test when we fine-tune the model in Part 5.

What We Chose Not to Do

Our implementation prioritizes clarity over performance. Understanding how tokenization works is more valuable than squeezing out extra speed. Some optimizations that production tokenizers use simply aren't necessary for learning.

Encoding Performance

Our sequential merge checking is straightforward but slow at large vocabulary sizes. Production tokenizers use trie-based lookup or cached encoding to speed this up. For learning purposes, the sequential approach is fine as you can actually see what's happening at each step.

String Representation

We store tokens as hex strings like <68><65><6c><6c><6f> for "hello". Production tokenizers use integers instead, storing merges as three numbers: (token_a, token_b) -> new_token. Strings waste memory and require parsing, but they're debuggable. You can look at your vocabulary and immediately understand what each token represents.

Vocabulary Management

We keep every merge we learn, even one-off patterns. Production tokenizers prune low-frequency merges. We also use a simple sampling optimization that isn't tuned to corpus statistics because it's good enough for learning, though not optimized for production.

Unicode and Multi-byte Characters

Byte-level encoding handles Unicode correctly by design. Every valid UTF-8 sequence encodes and decodes perfectly. Some production tokenizers optimize for this by treating multi-byte characters as atomic units or normalizing different Unicode representations of the same character. Our approach is simpler but less optimized for non-English text.

Why We Made These Choices

Alternative Rust libraries exist that address many of these issues. Tiktoken-rs provides Rust bindings to OpenAI's fast BPE implementation. Tokenizers is Hugging Face's production-grade tokenizer library with extensive features.

We're not using these because the goal is understanding, not optimization. Our implementation shows every step explicitly. You can trace exactly what happens during training and encoding. The code looks like the pseudocode you'd write on a whiteboard. The performance characteristics we see in benchmarks directly reflect algorithmic choices.

When you understand why encoding time grows dramatically with vocabulary size, you understand the fundamental computer science problem. When you see hex strings in the debugger, you understand what tokens actually represent. These insights are more valuable than a 10x speedup.

For production use, you'd absolutely use a highly optimized library. For learning, Feste works perfectly.

Next Steps

We now have a working tokenizer that converts between text and token IDs. It works correctly at multiple vocabulary sizes and gives us intuition for compression trade-offs. The tokenizer is the bridge between human-readable text and the numerical representations our model will process.

The remaining parts build the complete language model:

Part 2: Tensor Operations

In Part 2: Tensor Operations, Building an LLM From Scratch in Rust, we build the numerical foundation for neural networks. We'll implement matrix multiplication, element-wise operations, broadcasting, and activation functions like softmax. These operations let us manipulate high-dimensional arrays efficiently, the core of all deep learning.

Part 3: Model Architecture

In Part 3: Model Architecture, Building an LLM From Scratch in Rust, construct the GPT-2 Transformer architecture using our tensor operations. We'll implement multi-head attention, feed-forward layers, layer normalization, and residual connections. You'll see how 12 layers of transformers combine to process token sequences and predict the next token.

Part 4: Training Infrastructure

Next up, in Part 4: Training Infrastructure, Building an LLM From Scratch in Rust we set up the machinery for training. Data loading, batching, train/validation splits, and metrics logging. We'll build a flexible system that works for models of any size, preparing us to train everything from tiny experimental models to production-scale architectures.

Part 5: Training at Scale

In the final part of this series, Part 5: A Witless Fool, Building an LLM From Scratch in Rust we Train models at four different scales on Shakespeare's complete works. Start with a tiny 512-token vocabulary model that trains in minutes, then scale up to a 20,534-token vocabulary model that approaches production quality. Each scale teaches different lessons about convergence, overfitting, and computational trade-offs.ç

Running the Examples

The code for this chapter is in src/tokenizer.rs and the example in examples/01_train_tokenizers.rs. To run it yourself:

# Download Shakespeare corpus

curl -o shakespeare.txt https://www.gutenberg.org/files/100/100-0.txt

# Train tokenizers at multiple vocabulary sizes

cargo run --release --example 01_train_tokenizersThis will create a timestamped directory in data/ with all trained tokenizers and a summary of results.

What's Next

We've built a tokenizer that converts Shakespeare's text into numbers. We understand the trade-offs between vocabulary size, compression, and encoding speed. We've seen how merge rules compound to create longer and longer token sequences, and why larger vocabularies cost more to encode.

In the next part, we build the tensor operations that will let us manipulate these token sequences as high-dimensional arrays. We'll implement matrix multiplication, broadcasting, and activation functions. These are the numerical foundations that everything else sits on.

Then we'll add attention mechanisms, build the transformer stack, set up training, and train models at different scales. By the end of this series, you'll have a working language model trained on Shakespeare that you can explore interactively. More importantly, you'll understand how it works because you'll have seen every component implemented from first principles.

Image by Sambeetarts from pixabay