How-to Guide

Part 4: Training Infrastructure, Building an LLM From Scratch in Rust

January 26, 2026

Take Away:

In Part 1 of this series, we built a tokenizer that converts text into numbers. In Part 2, we implemented tensor operations that transform those numbers efficiently. In Part 3, we assembled those pieces into a complete transformer architecture. Now we implement the training infrastructure that transforms random weights into a working language model.

In Parts 1-3, we built a complete GPT-2 architecture. We can tokenize text, manipulate tensors, and run a forward pass through the model. Feed it "To be or not to be" and it produces logits over the vocabulary, its best guesses of what comes next. But those logits are meaningless because the weights are random.

This is the chapter where the model actually learns.

Training transforms random weights into patterns that predict language. The process is conceptually simple. Show the model some text, measure how wrong its predictions are, figure out which weights caused those mistakes, and nudge them in a direction that would have been less wrong. Repeat this thousands of times and the random weights become a coherent language model that in the case of Feste has learned what makes text sound like Shakespeare.

The interesting part is figuring out which weights to blame. When the model predicts "the" but should have predicted "thou", how do you trace that mistake back through 12 transformer layers, through attention mechanisms and feedforward networks, all the way to the specific weights that contributed to the error? That's what backpropagation does, and that's what we're implementing from scratch.

The math behind this is the chain rule from calculus. Our model is a chain of operations where the output of one feeds into the next. Token embeddings flow into attention, attention output flows into the Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP), MLP output flows into the next layer, and so on until we get final predictions. When we want to know how a weight deep in the network affected the final loss, we work backward through that chain. How did the loss depend on the logits? How did the logits depend on the final layer's output? How did that layer depend on the one before it? Work backward through the whole chain, and by the time you're done, you have gradients for every weight in the network. Each one tells you which way to turn that knob, and how hard.

We're implementing this explicitly for every component we built in Part 3. The attention backward pass, the layer norm backward pass, the MLP backward pass, all of it. Most frameworks hide this behind automatic differentiation where you call .backward() and gradients appear. Building it ourselves means we get to see exactly how training works at every step.

What Training Does

The training loop has a simple structure. Load a batch of text sequences, tokenized as we covered in Part 1. Run the forward pass as we covered in Part 3 to get predictions for the next token at each position. Compute the loss, which measures how far off those predictions were from the actual next tokens. Run the backward pass to compute gradients for every weight in the model. Use an optimizer to nudge the weights slightly based on those gradients. Then do it again with the next batch.

The forward pass produces predictions, and now we add everything else. The backward pass computes gradients that tell us how to improve. The optimizer uses those gradients to update weights intelligently rather than just subtracting them directly. Data loading handles batching and train/validation splits. Metrics track whether training is actually working. Checkpointing saves progress so you can stop and resume later.

By the end of this section, we'll train a model that might actually write like Shakespeare.

The Backward Pass

The forward pass flows data through the model. Remember that input embeddings become attention outputs, which become MLP outputs, which become final logits. Each operation transforms tensors using the current weights.

The backward pass flows gradients in the opposite direction. We start with the gradient of loss with respect to the logits and work our way back through each operation, computing gradients for both its parameters and its inputs. By the time we reach the embeddings, we have gradients for every weight in the model telling us which direction to adjust them.

Example: Linear Layer

Throughout the model, we keep doing the same operation. Attention computes Q by multiplying the input by a weight matrix. The MLP expands the hidden dimension by multiplying by a weight matrix. The output projection creates vocabulary logits by multiplying by a weight matrix. Every one of these is a linear layer, the fundamental building block of neural networks. A linear layer multiplies the input by a learned weight matrix, then adds a learned bias vector. In code: y = x @ W + b, where @ denotes matrix multiplication.

Here's a concrete example of how backpropagation works through a linear layer. During the forward pass, we transformed a token embedding into a query vector for attention. That transformation produced the output [2.5, 3.1]. After running the entire model and computing the loss, we discovered that if the transformation had produced [2.6, 3.0] instead, the prediction would have been better. The gradient grad_y = [0.1, -0.1] captures exactly this: increase the first output by 0.1, decrease the second by 0.1.

Now we need to figure out how to make that happen. Should we change the weights? Which ones? By how much? Should we tell the previous layer to change what it sent us? Three gradient formulas answer these questions.

The weight gradient grad_weight = x^T @ grad_y tells us which direction to adjust W. If the input was large when the output was wrong, those weights contributed more to the error. The bias gradient grad_bias does the same for the bias: since the same bias gets added everywhere, we sum the errors to see if it's consistently off. How much to actually adjust these parameters? That's the optimizer's job, which we'll get to later. The input gradient grad_x = grad_y @ W^T is different: it tells the previous layer how its output contributed to our error, so it can adjust its weights.

pub fn backward(&self, grad_out: &Tensor, cache: &LinearCache) -> LinearGradients {

let grad_weight = cache.x.transpose(-2, -1).matmul(grad_out);

let grad_bias = sum_across_positions(grad_out); // simplified

let grad_x = grad_out.matmul(&self.weight.transpose(-2, -1));

LinearGradients { weight: grad_weight, bias: grad_bias, x: grad_x }

}The code implements exactly what we described. Compute gradients for the weights using the cached input from the forward pass. Sum the output gradient to get the bias gradient (simplified in our example). And multiply the output gradient by the transposed weights to get the input gradient.

This pattern repeats for every layer in the model. During the backward pass, gradients arrive from the output side. We compute gradients for our own weights and for our input, then pass them along. The gradients flow backward through the entire network, one layer at a time.

Loss Computation

The loss function measures how wrong the model's predictions are. The model assigns a probability to every token in the vocabulary, using the current weights to predict how likely each token is to come next. We check the probability that was assigned to the correct token, a value between 0 and 1. The higher the probability the model gave to the correct token, the more accurate it was.

A negative logarithm converts these probabilities into loss values with a useful property: the curve is steep when probability is low, flat when probability is high. Conceptually, if the model assigned 0.8 to the correct token, the loss is about 0.22. If it only assigned 0.01, the loss jumps to 4.6. Perfect confidence in the right answer gives zero. The asymmetry means confident wrong predictions get punished severely: a model that says "99% sure it's X" when it's actually Y is penalized far more strongly. A confident wrong prediction means the weights have learned something false: that needs stronger correction than mere uncertainty.

We don't compute explicit probabilities. The model outputs logits, and we go straight to the log probability of the target token. The max subtraction trick we described in Part 2 keeps it numerically stable: subtract the max logit before exponentiating to avoid overflow.

pub fn compute_loss(&self, logits: &Tensor, targets: &[usize]) -> f32 {

for (i, &target) in targets.iter().enumerate() {

let logits_slice = &logits.data[logit_start..logit_start + vocab_size];

let max_logit = logits_slice.iter().fold(f32::NEG_INFINITY, |a, &b| a.max(b));

let exp_sum: f32 = logits_slice.iter().map(|&x| (x - max_logit).exp()).sum();

let log_prob = (target_logit - max_logit) - exp_sum.ln();

total_loss -= log_prob;

}

total_loss / seq_len as f32

}The gradient of cross-entropy tells us how to adjust each logit to reduce the loss. Say the model assigns probability 0.9 to the correct token. The gradient for that token is 0.9 - 1 = -0.1, a small negative value saying "increase this logit a little." If the model only assigned probability 0.1 to the correct token, the gradient is 0.1 - 1 = -0.9, a larger push saying "increase this logit a lot."

For incorrect tokens, the gradient is just their probability. A wrong token that got probability 0.3 has gradient 0.3, pushing to decrease that logit. A wrong token that got probability 0.01 barely gets pushed at all.

The gradients do exactly what you'd want: boost the correct answer, suppress the wrong ones, with the size of each adjustment proportional to how far off the current predictions are.

Layer Normalization Backward Pass

Layer normalization creates an interesting challenge for backpropagation. In the forward pass, we compute the mean and variance across each token's 768 features, subtract the mean, divide by the standard deviation, then apply learned scale and shift parameters. The tricky part is that every element in a normalized group depends on every other element through the shared mean and variance.

Think about what happens when you change one input value. The mean shifts, which changes all 768 normalized values. The variance changes too, which affects all 768 values again. When we backpropagate through layer normalization, we have to account for all these tangled dependencies.

Each input affects its output through three paths: directly through the normalization formula, indirectly through the mean, and indirectly through the variance. The gradient formula accounts for all three:

grad_x = (1/std) * (grad_x_norm - mean(grad_x_norm) - x_norm * mean(grad_x_norm * x_norm))The first term is the direct path. The second term subtracts out the influence that flowed through the mean. The third term subtracts out the influence that flowed through the variance.

The gradients for gamma and beta are simpler, there's no tangled dependencies there. Gamma multiplies each normalized value, so its gradient is the sum of the output gradient times the normalized values. Beta just adds to each value, so its gradient is just the sum of the output gradients.

The implementation computes all of these:

pub fn backward(&self, grad_out: &Tensor, cache: &LayerNormCache) -> LayerNormGradients {

// Compute grad_gamma and grad_beta by summing across positions

let grad_x_norm = grad_out.mul(&self.gamma);

for i in 0..seq_len {

let mean_grad = grad_x_norm_row.iter().sum::<f32>() / n_embd as f32;

let mean_grad_x = grad_x_norm_row.iter()

.zip(x_norm_row.iter())

.map(|(g, x)| g * x)

.sum::<f32>() / n_embd as f32;

for j in 0..n_embd {

grad_x_data[idx] = (grad_x_norm_row[j] - mean_grad - x_norm_row[j] * mean_grad_x) / std_val;

}

}

LayerNormGradients { gamma, beta, x }

}GELU Backward Pass

Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU) is simpler than layer normalization because each element is processed independently. When you change one input, only its corresponding output changes. No shared statistics, no coupling between elements.

The backward pass computes GELU's derivative. For each input value, we compute how much a small change to that input would affect the output, then multiply by the gradient flowing back from the next layer.

pub fn gelu_backward(grad_out: &Tensor, x: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

let grad_data: Vec<f32> = x

.data

.par_iter()

.zip(&grad_out.data)

.map(|(&x_val, &grad_val)| {

let grad_gelu = /* derivative of GELU at x_val */;

grad_val * grad_gelu

})

.collect();

Tensor::new(grad_data, x.shape.clone())

}Since every element is independent, we parallelize with Rayon. Each element's gradient depends only on its own input value and the gradient flowing back to it, so all the computations can happen simultaneously.

Attention Backward Pass

Attention is where transformers learn to understand context. Consider the Shakespeare line we used in Part 3: 'Better a witty fool than a foolish wit.' When the model learns that 'foolish' should attend back to 'fool' earlier in the sequence, or that 'wit' relates to 'witty', those patterns emerge because backpropagation adjusted the attention weights in the right direction. Understanding how gradients flow through attention means understanding how the model learns which words matter to each other.

This is the most intricate backward pass we'll implement. The forward pass chains together multiple operations: projecting the input into Q, K, and V, computing scaled dot products, applying softmax, combining values, and projecting back out. Gradients have to flow backward through all of that, and several of those operations involve matrix multiplications where we need gradients for both matrices.

We start at the output and work backward. The output projection is a linear layer, which we already know how to handle. That gives us gradients for the pre-projection attention output.

The attention output is a weighted sum of values: output = attention_weights @ V. This is a matrix multiplication, so backpropagating through it gives us two things. The gradient for V comes from multiplying the transposed attention weights by the output gradient. The gradient for the attention weights comes from multiplying the output gradient by the transposed V. Both matrices contributed to the output, so both need gradients.

Softmax is where the coupling appears, similar to layer normalization. Each attention weight in a row depends on all the scores in that row because softmax normalizes them to sum to one. When we backpropagate, changing one score would have affected all the weights in that row, so each gradient depends on the entire row of attention weights and their gradients:

for i in 0..seq_len {

let start = i * seq_len;

let end = start + seq_len;

let attn_row = &cache.attn_weights.data[start..end];

let grad_attn_row = &grad_attn_weights.data[start..end];

let dot_product: f32 = attn_row.iter()

.zip(grad_attn_row.iter())

.map(|(a, g)| a * g).sum();

for j in 0..seq_len {

let grad_score = attn_row[j] * (grad_attn_row[j] - dot_product);

grad_scores_data.push(grad_score);

}

}Now we have gradients for the scaled attention scores. These came from Q @ K^T divided by sqrt(d). Backpropagating through the scaling multiplies by that same factor. Backpropagating through Q @ K^T is another matrix multiplication backward pass, giving us gradients for both Q and K. The gradient for Q comes from multiplying the score gradients by K. The gradient for K comes from multiplying the transposed Q by the score gradients.

Finally, we backpropagate through the three projection layers that created Q, K, and V from the original input. Each is a linear layer. Since all three share the same input, the input gradient is the sum of the gradients flowing back through all three paths.

This is why the forward pass caches so much. We need the attention weights to backpropagate through the value combination. We need Q and K to backpropagate through the score computation. We need the original inputs to backpropagate through the projections. Every intermediate value from the forward pass gets used somewhere in this backward pass.

Residual Connections

Transformer blocks use residual connections where the input gets added to the output of each sublayer: y = x + sublayer(x). The input bypasses the transformation and gets added back in at the end.

The backward pass through a residual connection is simple. Gradients flow through both paths. The gradient for the addition just passes straight through unchanged, because adding something doesn't transform it. The sublayer backpropagates through its operations normally. The total gradient for the input is the sum of both paths: the gradient that flowed through the sublayer plus the gradient that skipped right past it.

pub fn backward(&self, grad_out: &Tensor, cache: &BlockCache) -> BlockGradients {

// Both paths receive the incoming gradient

let mut grad_x = grad_out.clone();

// MLP path with residual

let mlp_grads = self.mlp.backward(&grad_out, &cache.mlp_cache);

let ln2_grads = self.ln2.backward(&mlp_grads.x, &cache.ln2_cache);

grad_x = grad_x.add(&ln2_grads.x); // Residual: accumulate

// Attention path with residual

let attn_grads = self.attn.backward(&grad_x, &cache.attn_cache);

let ln1_grads = self.ln1.backward(&attn_grads.x, &cache.ln1_cache);

grad_x = grad_x.add(&ln1_grads.x); // Residual: accumulate

BlockGradients { /* ... */ }

}Residual connections are what make deep networks trainable at all. Without them, gradients can shrink as they flow backward through dozens of layers, eventually becoming too small to drive meaningful learning. The residual path gives gradients a highway that bypasses all the transformations. Even if some layer has terrible weights that would squash the gradient to nothing, the skip connection lets the signal through. This is why we can stack 12 transformer layers and still train effectively.

The Complete Backward Pass

Now we chain everything together. We've implemented backward passes for linear layers, layer normalization, GELU, attention, and residual connections. The complete model backward pass connects them all, flowing gradients from the loss back to every weight in the network.

pub fn backward(&self, logits: &Tensor, targets: &[usize], cache: &GPT2Cache) -> GPT2Gradients {

// Compute gradient of loss w.r.t. Logits

let grad_logits = compute_cross_entropy_gradient(logits, targets);

// Backprop through output projection and final layer norm

let mut grad_x = backprop_output_projection(&grad_logits, cache);

grad_x = self.ln_final.backward(&grad_x, &cache.ln_final_cache).x;

// Backprop through transformer blocks in reverse

let mut block_grads = Vec::new();

for (block, cache) in self.blocks.iter().zip(&cache.block_caches).rev() {

let grads = block.backward(&grad_x, cache);

grad_x = grads.x.clone();

block_grads.push(grads);

}

// Backprop to embeddings

let (grad_token_embedding, grad_position_embedding) =

backprop_to_embeddings(&grad_x, &cache.input_ids);

GPT2Gradients { /* all gradients */ }

}The gradient starts at the loss, flows backward through the output projection, through the final layer norm, then through each of the 12 transformer blocks in reverse order. Each block backpropagates through its MLP, its attention mechanism, and its layer norms, accumulating gradients for every weight matrix along the way. Finally the gradient reaches the embeddings.

When this function returns, every parameter in the model has a gradient. The token embeddings, position embeddings, all 12 layers of attention weights, all 12 layers of MLP weights, every gamma and beta in every layer norm, and the output projection. Millions of gradients, each one telling us how that particular parameter contributed to the prediction error.

This is what PyTorch hides behind .backward(). We built every piece of it explicitly, and now we can see exactly how a wrong prediction at the output propagates blame all the way back through the network to the individual weights that caused it.

Gradient Clipping

Sometimes gradients explode. The model encounters an unusual batch, or weights happen to amplify gradients as they flow backward, and suddenly you have gradient values in the thousands or millions. If you apply those gradients directly, you get a massive parameter update that destabilizes everything. The next forward pass produces NaN values, and training is ruined.

Gradient clipping is a simple safeguard. We compute the total magnitude of all gradients across all parameters using the L2 norm, which is just the square root of the sum of squared values. If that total magnitude exceeds a threshold, typically 1.0, we scale all the gradients down proportionally until the magnitude equals the threshold.

pub fn clip_gradients(grads: &mut GPT2Gradients, max_norm: f32) {

let norm = compute_grad_norm(grads);

if norm > max_norm {

let scale = max_norm / norm;

scale_all_gradients(grads, scale);

}

}We scale all gradients by the same factor. The direction of the update stays the same, and the relative sizes of different gradients stay the same. We're just capping how far we move in any single step. Most training steps won't trigger clipping at all, but when gradients do spike, clipping keeps training on track instead of blowing up.

Dropout Regularization

Shakespeare's complete works is a tiny dataset by modern standards. When you train on limited data, there's a risk the model memorizes specific examples rather than learning generalizable patterns. You can spot this happening when training loss keeps dropping but validation loss plateaus or starts climbing. The model is getting better at predicting text it has seen before while getting worse at predicting text it hasn't. That's called overfitting.

Dropout helps prevent this by making memorization unreliable. During training, we randomly zero out a fraction of the activations at each forward pass. With a dropout rate of 0.1, roughly 10% of the values flowing through each layer get set to zero, and which 10% changes every time.

Here's why this prevents memorization. If the model tries to memorize that a specific input produces a specific output by encoding that mapping in a particular set of neurons, dropout breaks the strategy. The next time that same input appears, different neurons are zeroed out. The memorized pathway is disrupted. The only patterns that survive dropout are ones encoded redundantly across many neurons, and those tend to be the general patterns that actually appear throughout the training data rather than the quirks of individual examples.

We apply dropout after the self-attention output and after the MLP in each transformer block. At inference time, dropout is disabled entirely and all activations flow through unchanged. You train with noise, but generate text with the full capacity of the model.

The AdamW Optimizer

We have gradients telling us how to improve. Now we need an optimizer that uses those gradients to update parameters intelligently. The original GPT-2 used Adam with L2 regularization. We use AdamW instead, which decouples weight decay from the gradient update. The difference is subtle but matters: L2 regularization adds the weight penalty to the gradient before Adam's adaptive scaling, which means heavily-updated parameters get less regularization. AdamW applies weight decay directly to the weights, independent of the gradient history. This works better in practice and has become the standard for training transformers. It's one of the few places where we deviate from the original GPT-2 implementation.

The simplest approach is basic gradient descent: subtract a scaled gradient from each parameter. This works, but it's slow and fragile. If the learning rate is too high, training oscillates wildly. Too low, and it takes forever to converge. Every parameter uses the same learning rate even though some might need larger updates than others.

AdamW solves these problems by tracking two quantities for each parameter. The first is a running average of recent gradients, which provides momentum. If gradients keep pointing the same direction, the optimizer builds up speed. If they oscillate, the momentum smooths things out. The second is a running average of squared gradients, which measures how much each parameter's gradient has been varying. Parameters with consistently large gradients get smaller effective learning rates. Parameters with small, stable gradients get larger ones.

m = beta1 * m + (1 - beta1) * gradient

v = beta2 * v + (1 - beta2) * gradient² The "W" in AdamW stands for weight decay, applied in a specific way. We shrink the weights slightly toward zero at each step, separately from the gradient update. This regularization helps the model generalize rather than memorize. Weight decay only applies to the actual weight matrices, not to biases or layer norm parameters.

pub fn adamw_update(

model: &mut TrainableGPT2,

grads: &GPT2Gradients,

optimizer: &mut AdamWOptimizer,

lr: f32,

weight_decay: f32,

) {

optimizer.step += 1;

let bias_correction1 = 1.0 - beta1.powf(step);

let bias_correction2 = 1.0 - beta2.powf(step);

// For each parameter (weights, biases, embeddings, etc.):

for i in 0..param.len() {

// Decoupled weight decay (skip for biases and layer norm)

param[i] *= 1.0 - lr * weight_decay;

// Update momentum estimate

m[i] = beta1 * m[i] + (1.0 - beta1) * grad[i];

// Update variance estimate

v[i] = beta2 * v[i] + (1.0 - beta2) * grad[i] * grad[i];

// Bias-corrected estimates

let m_hat = m[i] / bias_correction1;

let v_hat = v[i] / bias_correction2;

// Update parameter

param[i] -= lr * m_hat / (v_hat.sqrt() + epsilon);

}

}Early in training, m and v start at zero. Without correction, the first few updates would be artificially small since the running averages haven't warmed up yet. The bias correction terms compensate, ensuring updates are properly scaled from step one.

The hyperparameters beta1 and beta2 control how much history the running averages remember. Standard values are beta1 = 0.9 for momentum and beta2 = 0.95 for the variance estimate, though we tuned beta2 to 0.98 on Shakespeare and saw about 2.5% better validation perplexity. The learning rate is typically 3e-4 and weight decay is 0.1.

The implementation parallelizes updates for large tensors using Rayon. For small tensors under 1,000 elements, sequential updates avoid parallelization overhead.

Training Metrics

Watching metrics during training is one of the most satisfying parts of this whole process. You start with random weights producing garbage, and over thousands of steps you watch the numbers improve as the model learns Shakespeare.

A step is one batch of training data processed through the forward pass, backward pass, and weight update. For our Shakespeare dataset, training for 8,000 steps means seeing the same text dozens of times. The model learns by repetition, adjusting its weights a little after each batch.

Loss and Perplexity

Loss measures how wrong the predictions are, with lower being better. Cross-entropy loss for random guessing on a 1536-token vocabulary is about 7.3. A well-trained model should get this down to 2.0 to 4.0.

Perplexity is just exp(loss), and it has a nice interpretation: a perplexity of 50 means the model is about as uncertain as choosing randomly from 50 equally likely options. Random guessing gives perplexity equal to vocabulary size, so our 1536-token model starts around 1536 and should drop well below 100 as it learns.

We track both training loss and validation loss. Training loss measures predictions on text the model has seen. Validation loss measures predictions on held-out text it hasn't seen. When these diverge, with training loss dropping while validation loss plateaus, the model is memorizing rather than learning. That's the overfitting we discussed earlier.

Learning Rate Schedule

The learning rate controls how much we adjust weights after each batch. We start low during warmup, ramp up to a peak, then gradually decrease. Starting low might seem backwards when the model is completely wrong, but early on the gradients are chaotic and large updates make things worse. The warmup lets the optimizer find its footing before we open the throttle.

Sample Generation

The most fun metric isn't a number at all. Every few hundred steps, we generate sample text to see what the model has learned.

Remember what's happening here. We built a neural network that predicts the next token. At step 0, every weight in that network is random. The model has never seen text of any kind. We feed it "To be, or not to be" and ask what comes next, and it guesses randomly because that's all it can do.

Then we run the training loop. Forward pass, loss computation, backward pass, weight update. Thousands of times. Each pass nudges millions of weights in a direction that would have made better predictions.

Actual Training Output

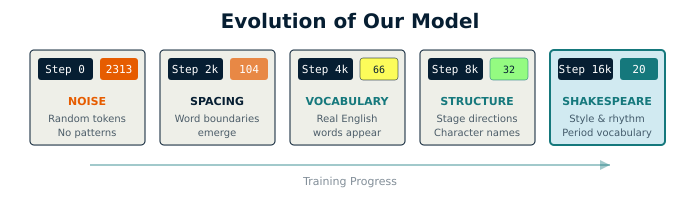

Below is real output from running the code we just built, training Feste on Shakespeare:

Step 0 Pure noise

Loss 7.75 | Perplexity 2313

"To be, or not to beI knowdoday�degentsidESAR."

Step 2000 Discovers spacing and word boundaries

Loss 4.65 | Perplexity 104

"To be, or not to beholle well ' attlthoughdring of return Thenchereiv"

Step 4000 Real English words emerge

Loss 4.19 | Perplexity 66

"To be, or not to be; and for the your sone,

shall he spar,

But heaven"

Step 8000 Learns play structure and character names

Loss 3.47 | Perplexity 32

"To be, or not to be.

Enter Perdgar.

HELENA.

Midds and all spirits "

Step 16000 Shakespearean rhythm and vocabulary

Loss 3.02 | Perplexity 20

"To be, or not to become you; if I must

If Caesar hath a wrong, thou k"

Watching this progression is more informative than any loss curve. You can see the model discover structure, then words, then formatting conventions, then stylistic patterns. Even at step 0, "ESAR" isn't random—it's a token in our vocabulary, a fragment of "CAESAR" surfacing through the noise. By step 8000, "Enter Perdgar" shows the model has learned that "Enter" followed by a name is a pattern in plays, even if Perdgar isn't a real character. HELENA is real though—she appears in both All's Well That Ends Well and A Midsummer Night's Dream. The model mixes invention with memory.

By step 16,000, the model has seen Shakespeare's complete works dozens of times, each pass refining its internal representation of what Shakespearean text sounds like. It is using "thou" and "hath" naturally. The line breaks fall where iambic pentameter would want them, suggesting the model is learning meter. The rhythm is right even when the meaning isn't.

We didn't program grammar rules. We didn't tell it about character names or stage directions. We just asked it to predict the next token over and over, and it figured out the rest.

The numbers track this progression. Loss measures prediction error. Perplexity is its exponential, roughly "how many tokens is the model choosing between." At step 0, a perplexity of 2,313 is actually worse than random guessing on our 1536-token vocabulary. The random weights aren't just unhelpful, they're actively interfering. By step 16,000, a perplexity of 20 means the model has narrowed down to about 20 plausible next tokens at each position. That's the difference between gibberish and coherent text.

Notice that training and validation loss both drop, but they diverge in later steps. In this snapshot, training perplexity is 20 while validation perplexity is 41. These numbers bounce around from step to step, so don't read too much into any single measurement. The pattern matters more than the specific values. When training loss consistently runs lower than validation loss, the model is predicting text it has seen better than text it hasn't. That's memorization creeping in. We want generalization, where the model learns patterns that work on any Shakespeare-like text, not just the exact sequences it trained on.

And this training run isn't finished. Validation loss is still dropping, which means the model is still learning. Part 5 will show what happens when we let it run to completion at multiple scales, from tiny models that train in minutes to full GPT-2 sized architectures that train for days.

Checkpointing

Training can take hours, days, even weeks. Checkpointing lets us save progress so we can stop and resume whenever we want, or roll back to an earlier point if we've overtrained.

A checkpoint saves everything needed to continue training exactly where you left off. The model weights, obviously. But also the optimizer state, which contains the momentum and variance estimates AdamW has accumulated for every parameter. Without the optimizer state, you'd resume with a cold optimizer that has forgotten everything it learned about which parameters need larger or smaller updates. We also save metadata like the current step and best validation loss.

pub struct Checkpoint {

pub model: TrainableGPT2,

pub optimizer: Option<AdamWOptimizer>,

pub tokenizer: Option<BPETokenizer>,

pub step: usize,

pub best_val_loss: f32,

pub best_val_step: usize,

}Feste uses a simple binary format: a header, version number, model configuration as JSON, then all tensors as length-prefixed arrays of floats. Production frameworks like PyTorch use standardized formats that allow sharing models between tools. We use a custom format because simplicity matters more than interoperability for a learning project.

Putting It Together

Everything we've built connects in a simple loop:

// Core training loop (simplified - see train_gpt2() for full implementation)

let mut loader = TextDataLoader::new(&text, &tokenizer, seq_len, batch_size);

let mut optimizer = AdamWOptimizer::new(&model);

let mut logger = TrainingLogger::new("training_log.csv")?;

for step in 0..num_steps {

let (inputs, targets) = loader.next_batch();

let (logits, cache) = model.forward(&inputs);

let loss = model.compute_loss(&logits, &targets);

let grads = model.backward(&logits, &targets, &cache);

clip_gradients(&mut grads, 1.0);

adamw_update(&mut model, &grads, &mut optimizer, learning_rate, weight_decay);

if step % 50 == 0 {

logger.log(step, learning_rate, loss, val_loss, None)?;

}

if step % 500 == 0 {

checkpoint.save(&format!("checkpoint_{}.bin", step))?;

}

}Each iteration loads a batch of text, runs the forward pass to get predictions, computes the loss to measure how wrong those predictions were, then runs the backward pass to figure out which weights to blame. We clip any explosive gradients, update the weights with AdamW, and occasionally log metrics and save checkpoints.

That's it. This loop runs thousands of times, and each iteration makes the model slightly better at predicting Shakespeare. The forward pass we built in Part 3. The backward pass we implemented earlier in this chapter, tracing gradients through attention, layer normalization, and feedforward networks. The optimizer we just covered. All of it comes together in these few lines.

The actual implementation includes more sophistication: learning rate scheduling with warmup and cosine decay, validation monitoring every 50 steps, early stopping when improvement stalls, and background checkpointing so we can resume from any point. Part 5 covers these in detail when we train at scale. For now, the core pattern is what matters: forward, backward, clip, update, repeat.

Performance

The training loop runs thousands of times, so the infrastructure needs to be reasonably fast. We use Rayon to parallelize gradient computations across CPU cores, and the cache-blocked matrix multiplication from Part 2 keeps all cores busy. For large tensors, parallelization provides 2x to 3x speedup. For small tensors, we skip parallelization because thread overhead costs more than the computation itself.

We're not chasing maximum performance. The goal is understanding how training works, and the implementation is fast enough to train real models on Shakespeare in reasonable time.

What We Haven't Implemented

Feste implements what we need to train working language models and understand the process. We have learning rate warmup, dropout, weight decay through AdamW, and gradient clipping. These are the core techniques that matter for training stability.

We skipped mixed precision training, which uses 16-bit floats for speed on GPUs with specialized hardware for half-precision math. Our CPU implementation uses 32-bit floats throughout because the speedup on CPUs is marginal and the added complexity isn't worth it for learning.

We also skipped distributed training across multiple machines. GPT-2 was trained on clusters of GPUs coordinated over a network. Our models train on a single machine using all available CPU cores through Rayon, which is plenty for Shakespeare-scale experiments.

Production training systems add many more optimizations. But the core loop is the same, and that's what we aim to understand with Feste.

Running the Example

The training infrastructure example demonstrates all the pieces working together:

cargo run --release --example 04_training_infrastructureThe example walks through the training pipeline components: training a BPE tokenizer on Shakespeare, creating batches with the data loader, splitting into training and validation sets, and demonstrating the training logger. It runs in seconds, letting you verify the infrastructure works before committing to longer training runs.

The training samples shown earlier in this chapter—watching the model discover spacing, then words, then character names—came from full training runs. Part 5 covers training at multiple scales, from tiny models that complete in minutes to full GPT-2 sized architectures. All outputs get saved to a timestamped directory in data/, including a CSV training log you can plot or analyze later.

What's Next

We have everything we need to train a language model from scratch. Tokenization from Part 1. Tensor operations from Part 2. The transformer architecture from Part 3. And now the complete training infrastructure: backpropagation through every layer, the AdamW optimizer, gradient clipping, data loading, metrics, and checkpointing.

You already saw a preview of what training looks like in the Sample Generation section. The model started with random noise and gradually learned spacing, then words, then character names and stage directions, then the rhythm of Shakespearean dialogue. That progression came from running the loop thousands of times.

Part 5 goes deeper. We'll train models at multiple scales, from a tiny 170K parameter model to a full GPT-2 sized architecture with 87 million parameters. We'll watch loss curves drop and perplexity improve. We'll see how different model sizes behave on the same dataset, and discover what happens when model capacity matches or exceeds the training data.

This is where everything comes together. Four chapters of building the machinery, and now we get to watch it learn.